In a Biting Letter to Basquiat in 1981, Edith Schloss Dragged the NYC Art Scene

Read this 3,700-word, hyper-critical letter discussing the work of Philip Guston, Anselm Kiefer, Nell Blaine, Bill King, Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, and several others: "Everyone seems to be proud of having no go, no oomph."

Edith Schloss in Pietrasanta, © The Estate of Edith Schloss (courtesy Artist Estate Studio)

In May 1981, painter Edith Schloss, who was a staff critic at the International Herald Tribune, published a review of the exhibition New York / New Wave at P.S. 1 (currently MoMA PS1). The review was the first mention ever of a rising young artist Jean-Michel Basquiat. Later that decade, Schloss penned a letter to Basquiat. She confesses her love for his work and offers him advice. And in a rambling, hyper-critical critique of the art scene in New York, she discusses the work of Philip Guston, Anselm Kiefer, Nell Blaine, Bill King, Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, Kenny Scharf, Susan Rothenberg, Eric Fischl, Donald Baechler, Jennifer Bartlett, Elizabeth Murray, Francesco Clemente, and others, as well as galleries, including Exit Art, Anina Nosei, and the East Village. This is that letter.

Letter to Jean-Michel Before It’s Too Late, or New York Art Now

When I saw your first work at P.S. 1 in 1981, I did something bad: on the bricks next to your drawings on typewriter paper I wrote with pencil: “I love these.”

Later, when I called up for more particulars, your manager, and the manager of the whole P.S.1 show, offered me your drawings for one hundred dollars each. But I said I was in the art selling business, not in the art buying business, and in this way I added another item to the long list of lost opportunities in my life. But je ne regrette rien, as my namesake sang.

Before I go any further, dear Jean-Michel, I must explain that I’m a painter, but as a hobby I write art reviews, and once I lived in New York and now I live in Europe.

Then I saw your big scrawly wiry things at the Whitney Biennial 1983.

How Graffiti Influenced Elizabeth Murray

Given some historical context, the impact graffiti had on the paintings Murray made during the 1980s is plain to see.

The 1980’s were a bodacious, hellacious, and most radical decade. Mötley Crüe got it right titling the era (and their greatest hits compilation album) the, “Decade of Decadence!” Intertwined with the rise of hip hop culture and a myriad international styles riffing off the energy of the streets in Los Angeles and New York City, graffiti exploded onto the scene. Artists in New York City in particular found inspiration in the tags, zips, and murals thrown up in endless rotation on subway cars and the buildings lining city streets.

As New York City slid towards bankruptcy in the mid-‘70s, graffiti, with its expressive, colorful, and vandalistic ways, amplified the voice of a significant subculture. “Only the very rich among New Yorkers could ignore the ubiquity of a new underground visual culture, which seemed to be rising like a red tide to cover public spaces: the spray-can art of the graffiti writers,” wrote curator Kirk Varnedoe in his 1990 essay “High & Low: Modern Art / Popular Culture,” “[Graffiti] suggested a city out of control, in which the most basic premises of civility had been surrendered.” Fierce competitive battles of new street styles covered subways and public spaces, and just at the moment the MTA made the elimination of graffiti a priority in the early ’80s, it was hitting the mainstream art world. Artists that once practiced surreptitiously began showing up in alternative spaces — first in the East Village, and then SoHo and 57th Street. The scene celebrated Keith Haring, Kenny Scharf, and wunderkind Jean-Michel Basquiat.

About the same time, Elizabeth Murray’s reputation was well on the rise. She was counted among a short list of artists credited for resuscitating painting when much of the art world proclaimed painting to be dead. By the late ‘70s she had all but abandoned the traditional rectangular canvas, opting for eccentric, irregularly shaped canvases. The twisting and skewing of her paintings would eventually introduce a three-dimensionality that opened a new space for painting. An important influence we can see in contemporary painters like Ruth Root and Justine Hill.

Although her childhood fascination with comics would remain a major influence throughout her four-decade career, it’s plain to see the impact graffiti had on the paintings Murray made during the ‘80s.

“Popular culture is one part of teeming life that everybody, all of us, are involved in,” Murray told filmmaker Michael Blackwood in 1990, for his film Art in an Age of Mass Culture. She continued:

Whether we know it or not, even if we try to withdraw ourselves from it, we are all really involved in it every day when we walk out into the streets and you hear a … guy walking by with his box blasting a rap song at you. Or in the middle of the subway. Or walking up Broadway. I mean, it’s pouring out at you all the time.

The Untold Story of Rauschenberg’s Earliest Champion

Among the reigning patriarchs of the New York School, the young Rauschenberg found his greatest and earliest champion in the painter Jack Tworkov.

Robert Rauschenberg “Jack Tworkov at the easel” (July, 1952) photo © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Collection of Estate of Jack Tworkov, New York

It is hard to imagine a time when Robert Rauschenberg wasn’t wildly admired. But it certainly was the case in the earliest days of his career, especially among the older generation of Abstract Expressionists who found him irreverent. They labeled his antics “anti-art,” and disregarded him altogether.

Rauschenberg was up against a stigma that dated back to the 1930s, held by artists like Pollock’s mentor, Thomas Hart Benton who believed that intellectuals, Marxists, and homosexuals had overtaken the American art scene. Abstraction equalled immorality in his view.

Yet the young Rauschenberg would find among the reigning patriarchs of the New York School, his greatest and earliest champion in the painter Jack Tworkov who was twenty-five years his senior.

Although drastically differing in temperaments, Tworkov and Rauschenberg both shared a common adversary: hundreds of years of European history, theory, and dominance in the arts. Tworkov and the New York painters of his generation argued from an existentialist platform “[declaring] their independence from all institutionalized concepts of the artist’s role in society,” wrote Dore Ashton. And they placed an importance on the individual over all else. “Painting is self-discovery,” Pollock told Selden Rodman in 1956, “Every good artist paints what he is.” Rauschenberg took this notion and ran with it.

Tworkov first became acquainted with Rauschenberg in the milieu of downtown New York. The journals of Tworkov, the letters of Rauschenberg, and two revelatory books by Calvin Tompkins, The Bride and the Bachelors (1965) and Off the Wall: Robert Rauschenberg and the art world of our time (1980) reveal the depth of their relatively unknown friendship.

An Ambitious Survey of the Titans of Abstract Expressionism

This expansive AbEx show is brash, irreverent, and unconstrained, just like the period it aims to express.

Jackson Pollock, “Blue Poles” (1952), enamel and aluminium paint with glass on canvas, 212.1 x 488.9 cm, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra (© The Pollock-Krasner Foundation ARS, NY and DACS, London 2016)

The titans of Abstract Expressionism are on view now at The Royal Academy of Arts in London. It’s a massive show comprising 163 works by 30 painters, sculptors, and photographers, and will likely go down in history as the largest loan exhibition of its kind.

It’s been close to 60 years since a show like this has been held on European soil (“New American Painting” toured eight European cities including the Tate, London, in 1958). The 12 colossal Beaux-Arts galleries can barely accommodate this explosive and ambitious survey of the prevailing personalities and perspectives associated with America’s greatest art movement. Curated by David Anfam, the movement’s leading expert, the show is brash, irreverent, and unconstrained, just like the period it aims to express. (For a tame chronological recap of the exhibition, buy the equally impressive publication that accompanies the show).

Never has a generation of avant-garde artists been more revered than those central to the Abstract Expressionist movement in America. Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, Barnett Newman, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still, and their counterparts Adolph Gottlieb, Philip Guston, Robert Motherwell, Ad Reinhardt, David Smith, and Jack Tworkov made history with their gestural works celebrating existentialism and raw humanity. It is their works that reign supreme in the show. Bonding through their time together on the WPA in the 30s and the comradery of The Club in the 50s, these artists made New York City the new capital of the art world with their new art.

Abstract Expressionism marked the first time in history that pure abstract art would rival old Modernism. “It was the moment when New York artists suddenly achieved self-awareness,” wrote the critic Thomas B. Hess in a profile about the scene for New York Magazine in December 1974, “realizing that they were together, and together could move ahead independently of a suffocating Paris-based aesthetic, which had dominated international markets of ideas and cash for over 150 years.”

A Designer Experiments with Digital Design, After 60 Years of Handcrafted Furniture

This expansive AbEx show is brash, irreverent, and unconstrained, just like the period it aims to express.

Wendell Castle, “Table-Chair-Stool” (1968) with “Serpentine Floor Lamp” (1965–67), installation view in ‘Wendell Castle Remastered’ at the Museum of Arts and Design, New York (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Designer Wendell Castle has made a career out of challenging the boundaries that define art and furniture. A new exhibition, Wendell Castle Remastered, on view at the Museum of Arts and Design, celebrates Castle’s many innovations, juxtaposing a selection of historically significant works against a group of new works that combine handcraftsmanship and digital technologies, including 3D scanning, 3D modeling, and computer-controlled milling. This is the first exhibition to examine Castle’s digitally crafted works.

While his predecessors, like George Nakashima, preferred the organic expressiveness of the surface of wood, Castle developed a sculptural technique in the early 1960s called “stack lamination,” where thick slabs of wood were glued together before being carved into dynamic biomorphic shapes. It was this unprecedented approach to furniture-making that has defined Castle’s six-decade career and made him a legend in the American art furniture movement.

“Scribe’s Stool” (1961–62) is one of the earliest works on view. Tall, thin, sinewy, and boney, the stool seems technically functional, yet its ungainly highchair-like structure would make sitting on it difficult. The elaborate, sweeping gestures of Art Nouveau were an obvious inspiration for this and other early works on view. “Scribe’s Stool,” above all, emphasizes Castle’s evolving wish that his furniture be thought of and collected on the same terms as sculpture.

“Blanket Chest” (1963) is Castle’s first stack-laminated cabinet. It’s a voluptuous, radish-shaped work — and a prelude, as Castle would soon master this technique, giving him the ability to realize even larger and more texturally animated, voluminous designs that recall the biomorphic works of Jean Arp and Henry Moore.

Castle’s “Serpentine Floor Lamp” (1965–67) seems unabashedly designed for the marketplace. It’s an elegant work in mahogany, that curves and bends and straightens itself. The work was actually the result of Castle manipulating and twisting a paper clip.

Minimalist Duets in Sculpture and Dance

This expansive AbEx show is brash, irreverent, and unconstrained, just like the period it aims to express.

Yvonne Rainer’s ‘Connecticut Rehearsal’ (1969) and Ronald Bladen’s “Cosmic Seed” (1977) (click to enlarge)

During the summer of 1960, dance artists Simone Forti, Nancy Meehan, and Yvonne Rainer rented rehearsal space at Dance Players on Sixth Avenue so they could improvise together. Sitting in on a rehearsal, the-soon-to-be-sculptor Robert Morris — who was married to Forti at the time — commented that the best moments were when they weren’t dancing.

So began the conversations among a historic group of dance makers that would grow to include Trisha Brown, Steve Paxton, Deborah and Alex Hay, and others, all of whom would make up the Judson Dance Theater. Their work broke with tradition and embraced movement based on process, improvisation, and causality. It represented not a single prevailing aesthetic but rather an effort to “preserve an ambiance of diversity and freedom,” wrote dance historian Sally Banes.

Seemingly simultaneously, sculptors like Morris, Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, George Sugarman, Tony Smith, and Anne Truitt also moved away from tradition in their field, abandoning the practice of modeling and carving and embracing a new kind of artistic autonomy — one which emphasized the clarity of the constructed object as well as the space created by it. Their manufactured and fabricated work came to be called minimalism.

Where Sculpture and Dance Meet: Minimalism from 1961 to 1979 is an exhibition at the Loretta Howard Gallery that explores this overlap. Curated by dancer–turned–dance critic Wendy Perron in collaboration with historian Julie Martin, the show pairs videos of historic performances of dances by Merce Cunningham, Lucinda Childs, Trisha Brown, Simone Forti, Yvonne Rainer, and (surprisingly) Robert Morris, with sculptures by Ronald Bladen, Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, Morris, and Andy Warhol, exploring the dialogue surrounding concurrent ideas of minimalism in dance, performance, and art.

“The label minimalist is a handy way of calling attention to a basic approach to composition,” wrote dance critic Jack Anderson in 1987 in the New York Times. I imagine the curators of the exhibition had Anderson’s handy approach in mind as they set about juxtaposing dance makers and sculptors from this historic period in American art.

But lumping a group of artists together as “minimalists” ignores how different they are from one another and simplifies the intentions behind their art. Dance makers during this time may have used movement sparingly and without embellishment, but that doesn’t mean they shared the same severity as, say, Donald Judd (and we know how much he rejected the minimalist label). Both Judd and Morris denied that their objects related to architecture, technology, or mathematics; instead, they emphasized their occupation with formal problems, with the “autonomous and literal nature of sculpture,” as Morris put it. Aptly for this show, their approach can be summed up by a statement from Yvonne Rainer: “In the studio, I work with aesthetics like a shoemaker works with leather.”

The Brute Classicism of Joel Perlman

Partial gallery view, Joel Perlman at Loretta Howard Gallery (all photographs by the author for Hyperallergic)

It’s been over twenty years since we’ve seen Joel Perlman’s large-scale sculptures on exhibition in New York City. The size and weight of his mighty works in welded steel can be a challenge to show, but Loretta Howard Gallery has pulled out all the stops with its current exhibition, bringing in five new large-scale works (four in welded steel and one in aluminum). The show also includes a small work in weathered steel, a hanging cast bronze, and a wall-mounted work in aluminum.

For much of the last forty years, Perlman has been creating towering sentinels in steel. His process has remained relatively unchanged since the very beginning: snapping huge industrial-grade planes of steel together with bold welds using a torch and his bare hands. Perlman is a stand-alone original preceded by Anthony Caro and David Smith.

Contemporary sculpture today can be defined by two extremes. One rooted in multiple points of reference as in the work of Paul McCarthy, which employs a mixed use of materials and crosses mediums where even the exhibition space can be appropriated as part of the ‘medium.’ The other rooted in singularity like the work of Richard Serra, whose massive large-scale works are specific to a direct exchange with the artwork. The first accentuates the artist’s strategy as a retort or response to an external societal change in the world. The second articulates the ambition of the individual through an attention to trueness in form and materials. The work of Joel Perlman belongs to the latter.

Perlman learned to weld alongside mechanics, farmers and trucker drivers at a night class offered at Ames Welding in downtown Ithaca while he was an undergraduate at Cornell University in the early 1960s. Welding was like “magic,” Perlman recalls, “You touch a rod to metal, there’s a flash and buzz, and two pieces become one.”

After the Miami Art Fairs: 9 Artists to Watch

MIAMI BEACH — One of the most exciting aspects of the art market is the discovery of new talent. In the early 1950s Ivan Karp and Leo Castelli marched down to derelict Fulton Street to meet up with the young Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. Not much later, historic figures like Holly Solomon and Paula Cooper climbed flight after flight of stairs navigating the cold-water flats of downtown to make their discoveries.

You never know what you’ll find at an art fair, like this corner of Cameron Gray’s installation at the Mike Weiss Gallery at Art Miami. (photograph by Hrag Vartanian for Hyperallergic)

MIAMI BEACH — One of the most exciting aspects of the art market is the discovery of new talent. In the early 1950s Ivan Karp and Leo Castelli marched down to derelict Fulton Street to meet up with the young Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. Not much later, historic figures like Holly Solomon and Paula Cooper climbed flight after flight of stairs navigating the cold-water flats of downtown to make their discoveries.

Today, the art fairs have become a nexus for “discovery.” Collectors, and moreover their art consultants, have come to rely almost solely on them. With hundreds upon hundreds of galleries and dealers descending upon the United States’s largest art fair last week, it can seem daunting to find that diamond of an artist in the rough that is Miami. Booth after booth and fairs upon fairs, how can anyone make scene of it all?

Discovering talent is a talent itself. As often is the case, experience and perseverance are key. Having followed the careers of hundreds of artists, it was excited to see a few making their Miami debut. Many of the artists I have selected here I have been following for a number of years, and it’s great to see them break out in Miami.

A Painter’s Retreat: Georgia O’Keeffe and Lake George

MIAMI BEACH — One of the most exciting aspects of the art market is the discovery of new talent. In the early 1950s Ivan Karp and Leo Castelli marched down to derelict Fulton Street to meet up with the young Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. Not much later, historic figures like Holly Solomon and Paula Cooper climbed flight after flight of stairs navigating the cold-water flats of downtown to make their discoveries.

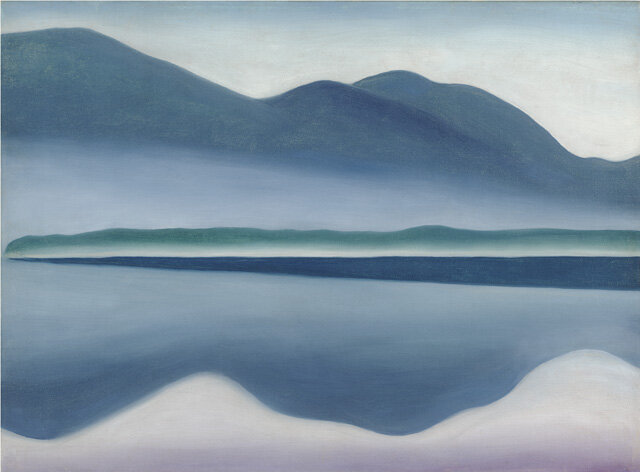

Lake George, 1922, oil on canvas, 16 ¼ x 22 in., San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Gift of Charlotte Mack (image © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York)

Glen Falls, NY — An ambitious exhibition on view this summer at the Hyde Collection is the first of its kind to explore the formative influence of Lake George on the art and life of Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986). O’Keeffe, the great Maiden of American Modernism, is celebrated most for the existential paintings she created out in the dry air of New Mexico, but as this exhibition attests, the works painted on the shore and in the hills around New York’s Lake George are among the most prolific and transformative of her seven-decade career.

The Hyde Collection is an extraordinary place, one of the few of its kind in upstate New York. A product of the golden age of the private art collector, it’s a prime example of the rare genre of museums created during the American Renaissance. Turned into a public museum by Charlotte Pruyn Hyde in 1952, she dedicated her estate and art collection to the community. Her two story house — the Hyde House — was constructed between 1910 and 1912 in the style of an Italian Renaissance palazzo and architecturally inspired by the Isabella Stewart Gardner’s Fenway Court in Boston.

The collection within consists of over 3,330 objects that span the history of Western art from Old Masters such as Sandro Botticelli, Rembrandt, Peter Paul Rubens, and El Greco’s “Portrait of St. James the Less” to modern masters such as Matisse and blue period Picasso in Mrs. Hyde’s Bedroom. The Hyde also contains a fine assortment of American art, with works by George Bellows, Thomas Eakins, Winslow Homer and — my favorite discovery — an Arthur B. Davies painting of Salt Lake, Utah, hanging in the Down Guest Bedroom. The O’Keeffe exhibition is located in the Woodward Gallery a modern building located adjacent to the Hyde House. It’s a fitting venue for an intimate look at O’Keeffe.

Modern Nature: Georgia O’Keeffe and Lake George offers sixty paintings dating from 1918-1934. Curated by Erin B. Coe (Chief Curator at the Hyde), and Barbara Buhler Lynes (former curator of the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum), the exhibit is divided into six themes: Landscapes, Barns and Buildings, Abstractions, Tree Portraits, From the Garden, and Lake George Souvenirs. The exhibition also includes significant loans from dozens of major collecting institutions from across the United States and is quite a coup for the Hyde.

America’s Grand Gestures Reign Supreme Again in Basel

Fifty-five years ago, the exhibition The New American Painting arrived at the Kunsthalle Basel. It was the first stop on a yearlong tour that touted the work of seventeen Abstract Expressionists before eight European countries — the first comprehensive exhibition to be sent to Europe showing the advanced tendencies in American painting.

Franz Kline’s “Provincetown II” (1959), oil on canvas, 93 x 79 in, heralds the return of postwar American painting at Art Basel. (image courtesy Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York)

BASEL, Switzerland — Fifty-five years ago, the exhibition The New American Painting arrived at the Kunsthalle Basel. It was the first stop on a yearlong tour that touted the work of seventeen Abstract Expressionists before eight European countries — the first comprehensive exhibition to be sent to Europe showing the advanced tendencies in American painting. Organized by the International Program of the Museum of Modern Art under the auspices of the International Council at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, the show was curated by Dorothy Miller and featured William Baziotes, James Brooks, Sam Francis, Arshile Gorky, Adolph Gottlieb, Philip Guston, Grace Hartigan, Franz Kline, Willem de Kooning, Robert Motherwell, Barnett Newman, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Theodoros Stamos, Clyfford Still, Bradley Walker Tomlin, and Jack Tworkov.

Director of MoMA at the time Alfred H. Barr, Jr. explained in a press release for the show that the artists in The New American Painting represented an individual liberty of style and expression. “None speaks for the others any more than he paints for the others,” he said. “Their individualism is uncompromising and as a matter of principle they do nothing deliberate in their work to make communication easy.”

The exhibition opened at the height of the Cold War, and for years it was rumored that it was all part of a secret CIA program aimed at promoting American ideals abroad — ideals that would later include the marketing of fast food and Walt Disney. The connection seemed improbable; after all, this was a period when the great majority of Americans disliked or even despised modern art. Even President Truman validated the popular view when he said: “If that’s art, then I’m a Hottentot.” However, the CIA connection was confirmed in a 1995 article published in the Independent.

Much time and history have passed since the heroic showing of The New American Painting. By the early 1960s, Pop art had surpassed Abstract Expression, and by the late 1960s, Minimalism and then Conceptual art had buried it. Today most of the art market still hedges its bets on contemporary art. So I was astonished to see postwar American painting and sculpture dominating the halls of the 44th edition of Art Basel. Could this be a response to the record sales recently recorded by New American Painting alums Barnett Newman and Jackson Pollock?

At Sotheby’s last month, Barnett Newman’s seminal painting “Onement VI,” a deep blue abstract composition from 1953, sold for $43.8 million, the result of a battle among five bidders. The price eclipsed Newman’s previous auction record by a margin of more than $20 million. The monumental 1953 painting was championed as one of the most important works by the artist ever to appear at auction and stands as a masterwork not only of Newman’s artistic enterprise, but of the entire Abstract Expressionist movement.

Black Mountain College Veteran’s Curiosity Spurs Her Art

The brilliant and inventive mind of Susan Weil is on full display at the Sundaram Tagore Gallery through June 15. At 83, Weil has lived at the epicenter of the New York art world since the early 1950s, and although her art has been relatively overshadowed by that of her contemporaries, Weil’s current show has the makings of her best.

“Susan Weil: Time’s Pace,” installation view at Sundaram Tagore Gallery, with “Georgia” (2013), left, and “Perspectacle” (2013), right (all photos by the author for Hyperallergic unless otherwise noted)

The brilliant and inventive mind of Susan Weil is on full display at the Sundaram Tagore Gallery through June 15. At 83, Weil has lived at the epicenter of the New York art world since the early 1950s, and although her art has been relatively overshadowed by that of her contemporaries, Weil’s current show has the makings of her best.

Weil was born in New York City in 1930 and grew up on Outer Island, NY. She came of age as an artist just as the postwar New York School was gaining steam. While attending the Académie Julian in Paris in 1948, she met Robert Rauschenberg, and for a time they became an inseparable pair. He followed her to Black Mountain College, both studying under Josef Albers. “I was still a teenager at Black Mountain,” Weil said in an interview years ago. “I had a defensive response to Albers’s authoritarian, exacting style. And yet I can see how his teachings have influenced me to this day.” Rauschenberg and Weil returned to New York and began participating in the extraordinary art scene of the time. “The interdisciplinary collaborations that we had enjoyed at Black Mountain were also blossoming in New York with events that combined dance, photography, and music,” Weil said. “Fences separating different disciplines came down.” Rauschenberg and Weil shared their thoughts and work with de Kooning, Kline, Tworkov, and others.

The pair spent the summer of 1949 on Outer Island. They bought a roll of blueprint paper and began staging compositions, exposing the paper to sunlight (Weil had experimented with cyanotypes since she was a child). The results of the collaboration were “thrilling,” according to the artist — Bonwit Teller used them in their department store windows; Life magazine published them in an article in April 1951; and the next month one was shown in the exhibition Abstraction in Photography at the Museum of Modern Art.

The Emotive Musculature of Resurrection

Stephen Petronio has been a creative force in the dance world for nearly 30 years. The most compelling aspect of Petronio’s career, and most intriguing for me, is his desire to collaborate, inviting composers, musicians, and visual artists to take on an idea and expand it within and beyond the dance.

Stephen Petronio (left) and artist Janine Antoni (right) set the scene as the audience takes their seats for “Like Lazarus Did” the new performance by Stephen Petronio Company (photograph by the author for Hyperallergic)

Stephen Petronio has been a creative force in the dance world for nearly 30 years. The most compelling aspect of Petronio’s career, and most intriguing for me, is his desire to collaborate, inviting composers, musicians, and visual artists to take on an idea and expand it within and beyond the dance.

For his current season at the Joyce, Petronio offers “Like Lazarus Did,” and with it heavy ideas of reincarnation and resurrection. His collaborators include composer Son Lux performing live with members of yMusic and The Young People’s Chorus of New York City, artist Janine Antoni, whose primary tool for sculpture has always been her own body, lighting by Ken Tabachnick, and costumes by H. Petal and Tara Subkoff.

I haven’t seen enough Petornio to say that I’m an expert. I approached the work as one obsessed with cross-disciplinary collaboration and with high expectations for the roles various art forms can play within a single production.

“Lazarus’ resurrection, the phoenix rising, and cycles of reincarnation are compelling ideas,” Petronio offers in his program notes, but getting across such heroic concepts can be a challenge even for the seasoned Petorino.

This isn’t Petronio’s first foray into the subject matter of death. Nearly 10 years ago his company presented “The King is Dead (Part I)” featuring stage design by Cindy Sherman, including slide projections showing mummified body parts with costumes by Manolo. A press release asserted that the dance concerns “the symbolic death of the male figure.”

A Blood on the Moon Fierceness: Fritz Bultman’s Paintings and Collages

“Painting deals with paradox,” wrote the artist Fritz Bultman in a notebook he titled Time and Nature, “For paradox offers us a tantalizing choice that is purely human and it is as a human document, not as a stylistic development, that art has a reason for existence.”

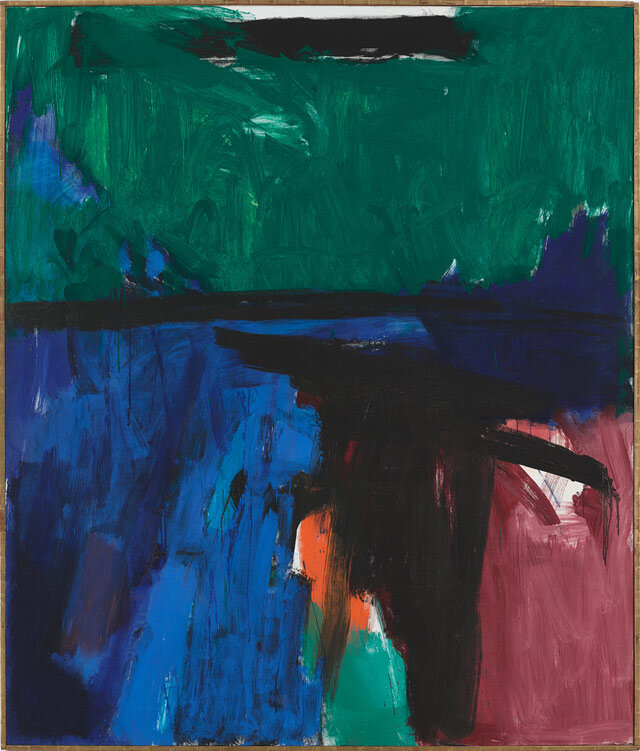

Fritz Blutman, “Rosa Park” ( 1958) (All images courtesy Estate of Fritz Bultman and Edelman Arts, New York)

“Painting deals with paradox,” wrote the artist Fritz Bultman in a notebook he titled Time and Nature, “For paradox offers us a tantalizing choice that is purely human and it is as a human document, not as a stylistic development, that art has a reason for existence.”

For Bultman, who unfortunately missed his photo-op as one of “The Irascibles” (the group of Abstract Expressionist painters made famous by a 1951 photograph in Life magazine), the paradox in painting was bridging nature and art. On view now at Edelman Arts is an exhibition of some of Bultman’s most important work, offering a rare opportunity to experience the artist’s struggle with this elusive paradox. The exhibition marks the first exhibition of Bultman’s work held in New York in nearly a decade. (The last exhibition was held in 2004 at Gallery Schlesinger, Bultman’s primary advocate since 1982.)

Fritz Bultman (1919–1985) was among the artists associated with the first generation of the New York School. He split his time between Provincetown and New York and counted among his close friends icons like Hans Hoffman, Lee Krasner, Stanley Kunitz, Robert Motherwell, Jackson Pollock, Tony Smith, and Jack Tworkov.

In 1950, Bultman signed the historic letter protesting the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s indifference to Abstract Expressionism and other forms of advanced art. Labeled by the press as “The Irascibles,” the group included almost all the artists who would achieve international acclaim as Abstract Expressionists. Unfortunately Bultman was studying sculpture in Italy at the time and missed the photo shoot for Nina Leen’s famous photograph, published in the January 15, 1951 issue of Life magazine. His absence from the iconic group portrait undoubtedly denied him a more prominent place in the history of post-war American art. Robert Motherwell proclaimed that of all the painters of his generation, Bultman was “the one [most] drastically and shockingly underrated.”

Less Is More at the Armory Show Modern

Let’s face it: navigating Armory Week and all its various satellites is a bitch. With so much art to see and endless booths to maneuver, it’s all very daunting. But we love it. Well, at least I love it.

Jean-Paul Riopelle, “Untitled (Iceberg Series)” (1977), oil on canvas, 10 3/5 × 13 4/5 in (courtesy Oriol Galería d’Art)

Let’s face it: navigating Armory Week and all its various satellites is a bitch. With so much art to see and endless booths to maneuver, it’s all very daunting. But we love it. Well, at least I love it.

Spontaneity and taxis are the two things I rely on the most. Spontaneity, because one should always open to possibilities, no matter what the schedule might dictate. Taxis, because who in their right mind wants to walk the five long-ass blocks to Pier 92, where the Armory Show’s Modern section was housed, from the subway (with a headwind off the Hudson River that somehow affects travel in both directions)?

A tiny black-and-white painting by the expressionist Jean-Paul Riopelle, “Untitled (Iceberg Series)” (1977), was the first work that grabbed me. On view at the booth of Oriol Galería d’Art, based in Barcelona, the painting measures only 10 by 13 inches but is incredibly seductive. Riopelle was known for his voluminous impasto, and this little work does not disappoint, with heavy lines of black carved deep into the back of the canvas with palette knife. Its simplistic, totemic gestures echo a range of history painting that could easily date back to the Lascaux caves. In 1972, Riopelle returned to his hometown of Québec and built a studio at Sainte-Marguerite-du-Lac-Masson. The stark northern landscapes there inspired his Iceberg Series of 1977 and 1978, to which this painting is attributed.

The Painterly Cravings of Larry Poons

Larry Poons might be considered one of the top painters working today, and he knows it. Over his five-decade career he has painted seminal works that have been shown and owned by an illustrious list of prominent private and museum collections all over the world.

Larry Poons, “Giordano Bruno” (2011) and “Untitled (012D-5)” (2012) (Image courtesy Jason Andrew)

Larry Poons might be considered one of the top painters working today, and he knows it. Over his five-decade career he has painted seminal works that have been shown and owned by an illustrious list of prominent private and museum collections all over the world. Critics and historians have written about his work for decades, with pages upon pages chronicling his modes and methods.

With so much history behind him, and considering that the artist is reaching nearly 80 years old, one might anticipate a lull in his creative output. But Poons remains one of our greatest painters. Like Mario Andretti lives for speed, Poons craves after paint. An exhibition of his most recent work, organized in tandem by the Loretta Howard Gallery and Danese gallery, is chock-full of the best painting on view in New York. Can you tell I’m a fan?

Poons’s work is about color. It’s been about color since his history-making dot paintings of the ’60s. And it’s been about color since his vigorous throw paintings of the ’70s. In the ’80s and ’90s, as surface and texture became prominent in his work, color, while it may seem to have taken a back seat to the physicality of the painting, still remained constant. And in recent years we’ve seen a welcome return to the brush.

“The Flying Blue Cat,” “Tycho Brahe,” and “Barreling” have expansive landscaped horizons and color staccatoed across the canvas in an all-over rhythm. They and the others in the show allude to a narrative but offer no wholly recognizable forms. Maelstroms of line and color tell a story more complicated than your typical “Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte.” But Poons isn’t a history painter by any means. “Spend some time with them,” he tells me. “It’s about the eye; it’s always been about the eye.”

A Playground for the Soul: Lost in Ann Hamilton’s World

For those craving a bit of the ephemeral this holiday season, artist Ann Hamilton has hung 42 swings from the wrought-iron trusses at the Park Avenue Armory as part of a new installation the artist titles “the event of a thread.”

The readers at Ann Hamilton’s “the event of a thread” (All photos by Jason Andrew unless otherwise noted)

For those craving a bit of the ephemeral this holiday season, artist Ann Hamilton has hung 42 swings from the wrought-iron trusses at the Park Avenue Armory as part of a new installation the artist titles “the event of a thread.”

Recognized for her visceral, temporal, and intricately crafted works, Hamilton is internationally known for her large-scale, multimedia installations. The title for Hamilton’s work at the Armory is borrowed from that great modern Arachne, Anni Albers, who reflected that all weaving traces back to “the event of a thread.” True to form, Hamilton expands upon a single, simple idea, weaving ropes and pulleys into a grand, kinetic, inspired, multi-layered experience.

At its core, the installation features two fields of suspended swings connected via ropes and pulleys to each other and to a massive white curtain that bisects the 55,000-square-foot Wade Thompson Drill Hall. Each swing has its counterpart on the other side and it is the visitor’s momentum on the swing that activates a rolling undulation of the curtain. The resultant movement brought on by one swing is enhanced when another visitor engages the corresponding swing on the opposite side. The movement of the curtain alone is mesmerizing and the beauty is that the curtain remains in a continual state of flux set in motion by the interaction of visitors.

“I can remember the feeling of swinging,” Hamilton states in a release about the installation, “how hard we would work for those split seconds […] when we felt momentarily free of gravity, a little hiccup of suspension when our hands loosened on the chain and our torsos raised off the seat. We were sailing, so inside the motion — time stopped — and then suddenly rushed again toward us. We would line up on the playground and try to touch the sky, alone together.”

Completing the installation is a succession of “attendants.” The first, two at a time, wear wool capes and read aloud at an enormous table near the drill hall’s entrance. Reading from a long scroll of text, their voices are broadcast by way of radio receivers packaged in brown paper bags and tied up with twine. The floor is scattered with these bags and visitors are able to carry the voices around with them.

During opening night, a young boy came running through the space yelling, “Look Mom! It’s my sack lunch.” Not just any sack lunch, though: This one spouts historic texts by philosophers (Aristotle, Johann Gottfried Herder, Giambattista Vico), naturalists (Charles Darwin and Ralph Waldo Emerson), an explorer (Captain William Dampier), as well as contemporary authors Susan Stewart and Lewis Hyde. Continuing the theme of transmission, there are 42 homing pigeons housed in cages surrounding the readers’ table.

Jackson Pollock and John Cage: An American Odd Couple

Jackson Pollock and John Cage are legends in American history. In the centennial year of both artists’ births, two exhibitions now on view in New York celebrate their work and underline the fact that even after their deaths, their influence continues to play an important role in how we understand, interpret, and even make art today.

Jackson Pollock and John Cage

Jackson Pollock and John Cage are legends in American history. In the centennial year of both artists’ births, two exhibitions now on view in New York celebrate their work and underline the fact that even after their deaths, their influence continues to play an important role in how we understand, interpret, and even make art today.

Jackson Pollock: A Centennial Exhibition at the Jason McCoy Gallery presents a selection of significant loans including paintings, works on paper, and objects by Pollock, ranging 1930 to the early 1950s. John Cage: The Sight of Silence at the National Academy Museum showcases sixty pieces, mostly watercolors,, created by Cage in the 1980s and 1990s, and also includes musical scores accompanied by recordings of his music, photographs, and videos of the revolutionary composer.

Pollock and Cage were aesthetic extremes of each other. Pollock sought to make paintings that were entirely an expression of his manic inner ego, whereas Cage fought to remove himself completely from the decision-making process involved in art. And yet, Pollock and Cage did have one thing in common. They shared a common adversary: hundreds of years of European history, theory, and dominance in the arts. So while Pollock fought to break from Braque, Cage battled to break from Beethoven.

Pollock and the Abstract Expressionists attempted to strike an emotional cord through grand gestures that reflected the subconscious mind. According to Caroline A. Jones in an article in Critical Inquiry, the movement became a celebration of the “masculine solitary whose staunchly heterosexual libido drove his brush,” with Pollock as the “quintessential hero of this powerful mythos.” Pollock and the New York painters argued from an existentialist platform, “[declaring] their independence from all institutionalized concepts of the artist’s role in society,” writes Dore Ashton in the book New York School. They placed an importance on the individual over all else. “Painting is self-discovery,” Pollock once said. “Every good artist paints what he is.”

The Brucennial Defends Nothing, Represents Everything

Since it’s founding in 2001, The Bruce High Quality Foundation has been using performance and pranks to critique the art world. The collective prides itself on “developing amateur solutions to professional challenges.” I’ve admired their irony, even envied their sense of anarchy.

A general view of the Brucennial (all photos by the author for Hyperallergic)

Since it’s founding in 2001, The Bruce High Quality Foundation has been using performance and pranks to critique the art world. The collective prides itself on “developing amateur solutions to professional challenges.” I’ve admired their irony, even envied their sense of anarchy.

In 2010 BHQF brought us the Brucennial. Organized by the then 23-year-old Vito Schnabel, the son of the artist Julian Schnabel. The show opened the same night as the reputable Whitney’s uptown Biennial, and I was one in the crowd that packed the space on West Broadway (which was provided to the artists courtesy of art collector Aby Rosen). I was also one of the many who after a few beers, and joining in on the ‘fuck you,’ tore up my ticket to the Whitney and spent the cab money I we saved on pizza at Two Boots.

According to the news release for the 2010 show, “420 artists from 911 countries” were shown and it added that the artist were “working in 666 disciplines to reclaim education as part of the artists’ ongoing practice beyond the principals of any one institution or experience.”

Tonight the Brucennial returned for its second edition. I hustled into the show at 5pm to avoid the lines (which went around the block in 2010). I was met with the expected paintings stacked floor to ceiling, sculpture loading up floor, Tina Turner playing on the speaker (I actually didn’t expect that!) and beer in bins.

As anticipated, it’s an enormous show. The big names like George Condo, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Cindy Sherman,and Richard Price stand out. They’re squeezed between the hundreds of no-name (there isn’t a label in sight) under-employed, under-recognized artists, gallery interns and Sotheby’s art handlers. It’s a massive show. An incredible undertaking. Absolute in its inclusiveness. It about the passion. The real. Hunting for quality just seems so uncouth among a crowd where everyone was drinking Pabst Blue Ribbon. The Brucennial defends nothing.

The End of the Legacy: Merce Cunningham’s Final Performances Begin Tonight

With a final series of performances beginning tonight and continuing through New Year’s Eve at the Park Avenue Armory, the Merce Cunningham Dance Company will close, ending nearly sixty years in operation.

“Antic Meet” (1958) with décor and costume by Robert Rauschenberg. (photo by Stephanie Berger)

Written jointly by Jason Andrew and Julia K. Gleich

With a final series of performances beginning tonight and continuing through New Year’s Eve at the Park Avenue Armory, the Merce Cunningham Dance Company will close, ending nearly sixty years in operation.

First formed at Black Mountain College in 1953, the Merce Cunningham Dance Company has changed the world of dance, not only through the development of a unique dance technique, but also in its embrace of cross-disciplinary collaboration with musicians and artists. Cunningham’s dances certainly stand alone in their use of space, time and the human form, but the experience of his choreography is magnified through his collaborators.

Cunningham’s most famous collaboration was with his life partner the composer/philosopher John Cage. Together, Cunningham and Cage proposed a number of radical innovations. One of the most famous and controversial of these concerned the relationship between dance and music, which they concluded can occur in the same time and space but can be created independently of one another.

“This continued to play out over six decades of Merce’s creative lifetime including a variety of other types of artists other than composers including visual artists, digital media artists, filmmakers, dancers, costume designers, and lighting designers,” remarked Trevor Carlson, Executive Director of the Cunningham Dance Foundation, at a panel hosted at Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) on Thursday, December 8. The panel invited four of the Company’s recent collaborators to discuss their work with Merce Cunningham: Daniel Arsham (set design), Gavin Bryars (composer), Paul Kaiser (designer), and Patricia Lent (dancer).

The sculptor Isamu Noguchi was among the earliest artists to team up with Cunningham and Cage, designing sets and costumes for Cunningham’s “The Season’s,” which was commissioned by Lincoln Kirstein for his Ballet Society in 1947. And when it was officially founded in the summer of 1953 at Black Mountain College, collaboration had become a vital signature of the company.

Pharma-Cultural Landscapes

During a brief two-week run, Storefront for Art and Architecture was transformed into a laboratory by the creative team of Harrison Atelier (HAt) in their latest iteration of dance-installation titled Pharmacophore: Architectural Placebo.

A view of the performance in Storefront from Kenmare Street (image courtesy Storefront)

During a brief two-week run, Storefront for Art and Architecture was transformed into a laboratory by the creative team of Harrison Atelier (HAt) in their latest iteration of dance-installation titled Pharmacophore: Architectural Placebo.

Conceived, dramaturged, directed and designed by the husband and wife team of Seth Harrison and Ariane Lourie Harrison the project explores “the cultural and philosophical economy that surrounds medicine, technology, and the human prospect.” Quite a heady agenda.

Architectural Placebo is the third installment in HAt’s Pharmacophore series of design-dance hybrids. HAt developed two prior versions: a ten-minute performance at Storefront in December 2010 with dance team Catherine Miller and James McGinn; and a full length performance at the Orpheus Theater in August 2011. For this iteration HAt collaborated with dancer/choreographer Silas Riener, who currently dances for Merce Cunningham Dance Company.

Bringing such lofty scientific terms and advanced terminology into a project certainly carries the risk of alienating an audience unaccustomed to such things. Pharmacophore is certainly unique in concept, but audiences don’t have to know much about the science of pharmacology or macrobiotics to appreciate this. The project is exceptionally designed and presented. And I’m sure that having a couple of dancers from the Cunningham company involved doesn’t hurt.

Architectural Placebo incorporates nearly every inch of the uniquely triangular ground-level space on Kenmare Street. It is perfectly suited for the complexities of HAt’s collaboration. Dancers Rashaun Mitchell, Jamie Scott and Melissa Toogood join Silas Riener and cellist Loren Dempster offers live accompaniment and original score.