“Karole Armitage, Bronislava Nijinska and their Philosophies of (a Contemporary) Ballet: Dancing into the Margins” in The Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Ballet

Features viewpoints from scholars, choreographers, dancers, and dance critics. Highlights contributions from choreographers around the globe. Includes a significant range of cultural and historical contexts in the late 20th and early 21st centuries

In distinction to many extant histories of ballet, The Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Ballet prioritizes connections between ballet communities as it interweaves chapters by scholars, critics, choreographers, and working professional dancers. The book looks at the many ways ballet functions as a global practice in the 21st century, providing new perspectives on ballet's past, present, and future. As an effort to dismantle the linearity of academic canons, the fifty-three chapters within provide multiple entry points for readers to engage in balletic discourse. With an emphasis on composition and process alongside dances created, and the assertion that contemporary ballet is a definitive era, the book carves out space for critical inquiry. Many of the chapters consider whether or not ballet can reconcile its past and actually become present, while others see ballet as flexible and willing to be remolded at the hands of those with tools to do so.

Co-written with Molly Faulkner, PhD.

Farrugia-Kriel, Kathrina and Jill Nunes-Jensen, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Ballet, Oxford University Press, 2021.

“Should there be a female ballet canon? Seven Radical Acts of Inclusion” in (Re:) Claiming Ballet

Seven Radical Acts explores the pitfalls and strengths surrounding the notion of a female ballet canon.

The collection of essays demonstrates that ballet is not a single White Western dance form but has been shaped by a range of other cultures. In so doing, the authors open a conversation and contribute to the discourse beyond the vantage point of mainstream to look at such issues as homosexuality and race. And to demonstrate that ballet’s denial of the first and exclusion of the second needs rethinking.

This is an important contribution to dance scholarship. The contributors include professional ballet dancers and teachers, choreographers, and dance scholars in the UK, Europe and the USA to give a three dimensional overview of the field of ballet beyond the traditional mainstream.

It sets out to acknowledge the alternative and parallel influences that have shaped the culture of ballet and demonstrates they are alive, kicking, and have a rich history. Ballet is complex and encompasses individuals and communities, often invisiblized, but who have contributed to the diaspora of ballet in the 21st Century. It will initiate conversations and contribute to discourses about the panorama of ballet beyond the narrow vantage point of the mainstream - white, patriarchal, Eurocentric, heterosexual constructs of gender, race and class.

This book is certain to be a much-valued resource within the field of ballet studies, as well as an important contribution to dance scholarship more broadly. It has an original focus and brings together issues more commonly addressed only in journals, where issues of race are frequently discussed.

The primary market will be academic. It will appeal to academics, researchers, scholars and students working and studying in dance, theatre and performance arts, and cultural studies. It will also be of interest to dance professionals and practitioners.

Academics and students interested in the intersection of gender, race and dance may also find it interesting.

Co-written with Molly Faulkner, PhD.

Akinleye, Adesola, ed. (Re)Claiming Ballet, an anthology. Intellect Books, 2020.

Put Your Best Face Forward

Artist Estate Studio Cofounder, Julia Gleich was interviewed by Garnet Henderson about how important facial expressions are and how often they’re forgotten about in dance.

Artist Estate Studio Cofounder, Julia Gleich was interviewed by Garnet Henderson about how important facial expressions are and how often they’re forgotten about in dance.

Put Your Best Face Forward

Develop a more expressive, versatile face

BY GARNET HENDERSON

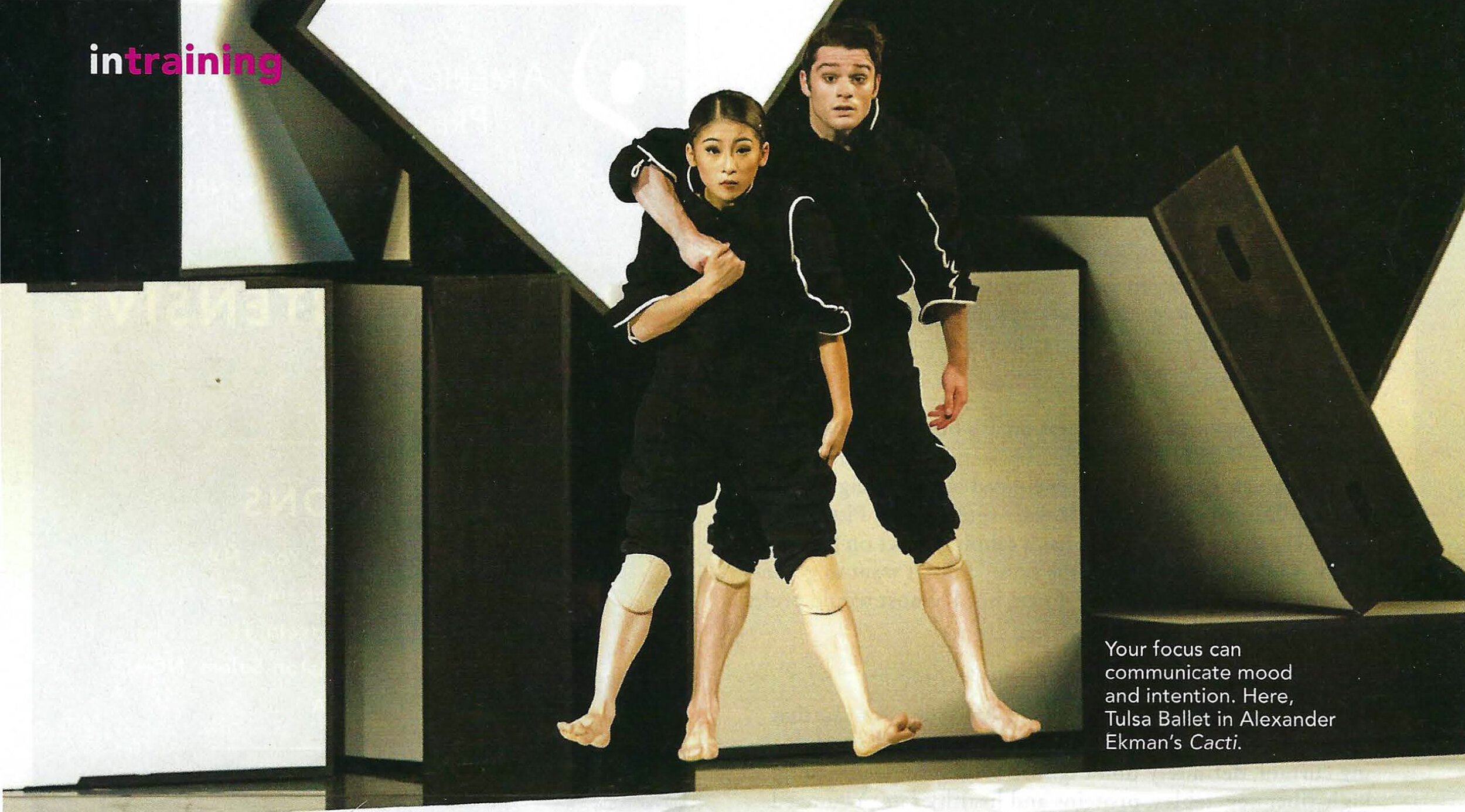

A dancer's face can be a powerful tool to convey personality, emotion or character, and it's often the first thing noticed by the audience. Yet dancers sometimes forget about it entirely because they are so focused on the rest of the body. Making better use of your face can add nuance to your roles, and help you forge a deeper connection to the audience.

Know Your Motivation

DO

Acknowledge that different styles call for different approaches. "Limon is very natural. It's all about breath, and having an open face," says Julia Gleich, faculty member at Trinity Laban in London. "Graham is much more about longing and urgency. It's a more narrow focus, like there are laser beams coming out of the eyes." Dancers can practice expressing different movement qualities with the face as well as the body. "A perfect example is something that's strongly percussive, like a tango," says Gleich. "How can you reflect that dramatic, powerful, explosive quality in the face?"

DO

Take acting classes. Whether or not you're doing character work, they can help you gain better control over your facial expressions and make choices about what to do with your face.

DON’T

Let your face be blank, unless it's a choreographic choice. "Sometimes in contemporary dance it looks like the body is moving, but the face doesn't know it," says Gleich. Remember that you are still yourself while in the studio. "You don't have to check your whole life at the door," she says.

DON’T

Go overboard. For example, while hip hop requires a different type of facial expression than ballet or modern, says Steven Vilsaint, a hip-hop teacher at Accent Dance NYC, it should still be nuanced. Over-the-top faces don't always communicate a feeling or narrative to an audience. "Dance is a language," he says. "Make sure you're telling the story you want to tell."

The Case Against Versatility: Why Being A Jack-of-All-Trades Dancer Won't Help You

These days, everyone tells you how important it is to be versatile. But what if you're convinced there's just one style that's right for you? It can be tough to balance a deep interest in a single specialty and still meet many choreographers' expectations.

Julia K. Gleich suggests branching out to discover what you don't want. Photo courtesy Brooklyn Ballet

Excerpt:

These days, everyone tells you how important it is to be versatile. But what if you're convinced there's just one style that's right for you? It can be tough to balance a deep interest in a single specialty and still meet many choreographers' expectations. Luckily, you don't have to choose between all in or all over the place, as long as you follow your interests thoughtfully.

Take Time to Find Your Style

When you're young, study a little of everything—that's how you'll figure out what you like to do and where you really shine. No one technique can provide everything you need, says Julia K. Gleich, founder of contemporary ballet company Gleich Dances and a frequent teacher at Peridance Capezio Center. "If you're confined to a single aesthetic, you're missing out on a wider vision of the world that informs your art."

Ask yourself if you're being stubborn about specializing just to stay in your comfort zone. "If you're sticking to a single technique out of fear of the unknown, you're in trouble," says Gleich. Choreographer Al Blackstone agrees: "You may think you know what you want, but allow yourself to be wrong," he says. You may even choose to diversify your training to be sure that your specialty is the style for you. "You need knowledge of other forms to understand your own better and know what you don't want to do," says Gleich. "So if you're convinced you want to pursue Balanchine, take class from a few Cecchetti teachers, too."

She’s Sayin'

Gleich writes about her experience meeting and observing Annabelle Lopez-Ochoa while she created “Broken Wings” for English National Ballet’s “She Said” all-female triple bill. Gleich’s Choreographer Observership was awarded by OneDanceUK.

Gleich writes about her experience meeting and observing Annabelle Lopez-Ochoa while she created “Broken Wings” for English National Ballet’s “She Said” all-female triple bill. Gleich’s Choreographer Observership was awarded by OneDanceUK.

“Illuminations” in SDHS Conversations Across the Field of Dance Studies: Network of Pointes, Volume XXXV

I trained in NYC in the heyday of ballet, in the 1970s, when New York was a dance world capital. A student of Melissa Hayden, I studied with David Howard, Robert Denvers, Willie Berman, and many others.

Photo: Jason Andrew

I trained in NYC in the heyday of ballet, in the 1970s, when New York was a dance world capital. A student of Melissa Hayden, I studied with David Howard, Robert Denvers, Willie Berman, and many others. In briefly attending the School of American Ballet, I was in class with dancers from NYCB and ABT, defectors from Russia, and the energy was inspiring and thrilling. For me, ballet was just ballet. It was Balanchine and Petipa, Robbins and Joffrey, Tharp and De Mille. Those were also the days of the Joffrey company in NYC and they had a strong influence on my attitude toward ballet with a somewhat inclusive company model dancers of different shapes, sizes, and colors, and a varied repertory that included ballet to rock music. In hindsight, I was embracing a contemporary aesthetic, but was in class all the time with "ballet" dancers. Rarely do I remember being mired in a singular style or sticking to narrow, rigid, classical ideals. But I never would have called our dancing contemporary, nor would I have called it classical. It was simply ballet.

Two decades later, while teaching and choreographing in New York City in the 1990s, participated in a ballet choreography master class. At the time I identified with ballet as my medium, but upon showing my first study it was suggested that what I had made was "not ballet" but "something more modern like Graham or Cunningham." Naturally I responded with great pleasure and said, "yes, it's like 'me'!" The master teacher was not impressed by my response and left me to ponder why I was taking the workshop in the first place. I thought I knew why: I came from ballet and used pointe work. My dancers were usually ballet trained and I felt I had not immersed myself in modern approaches to creativity. But what I produced seemed not “ballet enough.”

This furthered questions about my identity as a choreographer, teacher, and dancer. For my next project in 1999 I hired dancers from a program that was focused on modern dance. The piece was on pointe and quickly realized there were unique differences in these dancers. They were less vertical, but also less daring en pointe and philosophically burdened by a need to solidify a modern identity within the piece. This experience influenced my approach to teach ballet, especially at the higher education level. What I wanted for my students was reflected in a technique that was neither of the ballet or the modern/contemporary extremes, but based in movement invention utilizing a ballet vocabulary. Choreographically, want what is valued in both the modern and ballet worlds (or contemporary and classical?). Today I choose to work with ballet dancers who are strong on pointe and open to new methods. And teach dancers to be hireable. We don't know what new idea is going to capture the imagination of dance audiences next.

The End of the Legacy: Merce Cunningham’s Final Performances Begin Tonight

With a final series of performances beginning tonight and continuing through New Year’s Eve at the Park Avenue Armory, the Merce Cunningham Dance Company will close, ending nearly sixty years in operation.

“Antic Meet” (1958) with décor and costume by Robert Rauschenberg. (photo by Stephanie Berger)

Written jointly by Jason Andrew and Julia K. Gleich

With a final series of performances beginning tonight and continuing through New Year’s Eve at the Park Avenue Armory, the Merce Cunningham Dance Company will close, ending nearly sixty years in operation.

First formed at Black Mountain College in 1953, the Merce Cunningham Dance Company has changed the world of dance, not only through the development of a unique dance technique, but also in its embrace of cross-disciplinary collaboration with musicians and artists. Cunningham’s dances certainly stand alone in their use of space, time and the human form, but the experience of his choreography is magnified through his collaborators.

Cunningham’s most famous collaboration was with his life partner the composer/philosopher John Cage. Together, Cunningham and Cage proposed a number of radical innovations. One of the most famous and controversial of these concerned the relationship between dance and music, which they concluded can occur in the same time and space but can be created independently of one another.

“This continued to play out over six decades of Merce’s creative lifetime including a variety of other types of artists other than composers including visual artists, digital media artists, filmmakers, dancers, costume designers, and lighting designers,” remarked Trevor Carlson, Executive Director of the Cunningham Dance Foundation, at a panel hosted at Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) on Thursday, December 8. The panel invited four of the Company’s recent collaborators to discuss their work with Merce Cunningham: Daniel Arsham (set design), Gavin Bryars (composer), Paul Kaiser (designer), and Patricia Lent (dancer).

The sculptor Isamu Noguchi was among the earliest artists to team up with Cunningham and Cage, designing sets and costumes for Cunningham’s “The Season’s,” which was commissioned by Lincoln Kirstein for his Ballet Society in 1947. And when it was officially founded in the summer of 1953 at Black Mountain College, collaboration had become a vital signature of the company.

“Generating, analysing, and organizing movement using the mathematical concepts of vectors” in The Dynamic Body in Space

Generating, analyzing, and organizing movement using the mathematical concepts of vectors.

Excerpt:

Dance can be seen as simple combinations of directed energy. This applies to motion as well as apparent stillness. Directed energy could be a pathway or line of direction with a length or magnitude, a vector. A vector is a mathematical concept, usually represented by a line with an arrow at one end. In its simplest geometric sense, a vector has only direction and magnitude (length).

Vectors allow the possibility to strip dance down to its essential properties in similar ways to Laban's development of Space Harmony and more. "One of the things that gives mathematics its power is the shedding of attributes that turn out to be nonessential. .. " (Hoffmann 1966 p. 10) In developing this research integrating mathematics, kinesiology, physics and dance, there are implications for pedagogic practice as well as analysis and choreographic invention.

Preston-Dunlop, Valerie, and Lesley-Anne Sayers, eds. The Dynamic Body in Space: Exploring and Developing Rudolf Laban's Ideas for the 21st Century. Alton, Hampshire: Dance Books, 2010.

Reports from Around the World. Not Just Any Body & Soul, The Hague

“Reports from Around the World.” Not Just Any Body & Soul, The Hague, IADMS Newsletter Vol. 11 No. 2. Spring 2004.

“Exorcising Ghosts of Dance” in Healthier Dancer Magazine

“Exorcising Ghosts of Dance.” DanceUK Healthier Dancer Magazine. Spring 2004.

“Ode to Alexander Bennett” in Ballet Review

“Ode to Alexander Bennett” Ballet Review. Winter 2002.