Judy Pfaff: Busting pictures to hell

De Kooning once said, “Every so often a painter has to destroy painting.” Cezanne did it. Picasso did it. Then there was Pollock. As de Kooning put it, he “busted our idea of a picture to hell.”

Judy Pfaff, Quartet One, 2018; Photographic inspired digital image, wire frame, acrylic, melted plastic, aluminum discs, fungus, paper, glitter, Styrofoam, fluorescent light, drawing in artist’s frame; 120.75 x 156 x 32 inches.jpg

Contributed by Jason Andrew

De Kooning once said, “Every so often a painter has to destroy painting.” Cezanne did it. Picasso did it. Then there was Pollock. As de Kooning put it, he “busted our idea of a picture to hell.” And after him came Judy Pfaff. Ever since her three-wall breakout show in the backroom of Artists Space in 1974, she has been at odds with the stringent attitudes and moral fervor that burdened postwar painting. In a suite of four new wall-sized works at Miles McEnery Gallery, Pfaff draws inspiration from a lifelong interest in the natural and the spiritual realms.

Straight out of Al Held’s classroom at Yale, Pfaff took a sculptural approach to painting. Strong color, bold three-dimensional accents, and a strong impulse towards architecture have been the currents driving her art. “I’m at war with conventions,” Pfaff said in an interview with Irving Sandler in 1982. Because her work escapes definition, her eclectic, freewheeling gestalt has been mistaken for artistic gesture linked to the Abstract Expressionists. But the visual opulence of her work is more appropriately described as a kind of global orchestration of ideas.

I’ve always thought that she was at her best when she fully embraced her unbridled effervescence and cast aside the conventional limits of an exhibition space (and the marketplace, for that matter), as she did in first installation of hers that I saw at the André Emmerich Gallery in 1997. When it’s uncanvassed and unbound, her work conveys a risk-courting adventurousness that is all the more compelling because it edges toward the ephemeral – like performance and indeed life itself. This disposition cuts sharply against the “objectness” of painting.

Jenny Snider: Mutiny, rebellion, the experience of life

Jenny Snider is a storyteller. The content and form of her art come from a variety of sources: history, popular culture, politics, and art itself in the form of grid-based abstraction representing natural and mechanical forms.

Jenny Snider, Noir, 1995, oil on canvas board, 20 x 24 inches

Contributed by Jason Andrew

Jenny Snider is a storyteller. The content and form of her art come from a variety of sources: history, popular culture, politics, and art itself in the form of grid-based abstraction representing natural and mechanical forms. But singularly, she is interested in “describing the experience of the life I know and imagine, all melding with the books I’ve read, the movies I’ve seen, the cars we drove, the views from my window.” A mini-survey of Snider’s work on view at Edward Thorp Gallery highlights the artist’s witty, gritty, and elusive career with selected works from the 1970s to the present.

Mutiny, rebellion, the downcast, and the outcast have been themes underlying Snider’s work. The earliest piece is from 1972 – a gridded ink drawing on rice paper titled Fuji. For Snider, much like her Yale classmate Jennifer Bartlett, the grid came to support an open construct. The recurrence of the grid for her is reflective of “conversations in consciousness raising groups, of being a woman and the struggle between domestic and professional.”

Snider cites personal experience in Master Class (1973), painted at a time when the artist was studying the 1887-1888 Shanghai Edition of The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting, and when Picasso passed away. “Picasso died and there was a lengthy obit in The New York Times celebrating his big life,” Snider said. “I was so angry. His shadow cast over us all.” The beautifully rendered meditative studies she had been making gave way to an imposing bust portrait of one of the 20th century’s greatest misogynists. Beyond the portrait, and perhaps in an arch effort to outshine the master, Snider penned her own (hilarious) obituary that was later published in the satirical issue of Heresies edited by Martha Wilson.

Katherine Bradford: Deep image painting

The art of Katherine Bradford, on view at Canada through October 21, is deep image painting. Her often heroic imagery and surrealist leaps echo a floating world, one that narratively exists between the real and the dream. Each work has a self-conscious spiritualist language that represents a developing poetic stance – a story that starts, but never finishes its tale.

Katherine Bradford, Water Lady, 2018, acrylic on canvas, 80 x 68 inches

Contributed by Jason Andrew

The art of Katherine Bradford, on view at Canada through October 21, is deep image painting. Her often heroic imagery and surrealist leaps echo a floating world, one that narratively exists between the real and the dream. Each work has a self-conscious spiritualist language that represents a developing poetic stance – a story that starts, but never finishes its tale.

Take the painting Water Lady, a monolithic central figure with a glowing red rectangle on the chest, kneels in a pool of water. In a cross-body reach, the figure collects water as it pours from a bottle suspended in mid-air. It’s a dreamlike picture in which identity is represented not just by the faceless pink painted human form, but also by the collective symbolic setting. What’s most arresting about this picture, aside from the odd outstretched arms that occupy the bottom margin of the canvas, is that it situates us in the middle of the narrative and prompts us to ask, “How did we get here?” and “How will it end?” These questions are inherent in all of Bradford’s work.

The term deep image was coined in the early 1960s by American poets Jerome Rothenberg and Robert Kelly to describe their own writing style, which was characterized by a resonant and heroic tone, unexpected juxtapositions, and surrealist leaps. It was a style inspired as much by Charles Olson’s projectivism as by the cante jondo or deep song and the poetry of Federico García Lorca.

For Rothenberg, the deep image poem reflected two realities: first, the empirical world of the naïve realist of what we know; second, the hidden floating world of what is to be discovered. The first world both hides and leads into the second, which in turn as a lure and a repository of dreams. For Rothenberg, deep work is perception and vision, and the poem is the movement between them. For Bradford, paint is instead the vehicle.

At 76, Bradford’s personal and empathic style of figurative abstraction dives deep into human psyche. Over the years she has introduced themes that range from Superman and swimmers to Titanic-like ocean liners. As a master mark-maker with a five-inch brush, her work has been placed in the broad context of Abstract Expressionism. I think it pleases Bradford that we can approach her work from an abstract point of view, but the very complex and deeply psychological pictures tell us more influences are afoot.

Bradford may be a more direct artistic descendant of the late, great Elizabeth Murray, who famously brought subject matter back into abstraction. Bradford also channels Joan Brown, whose work conveyed a kind of ipso facto feminism. And Bradford borrows the poetic excess found in the paintings by Alice Neel. In all cases, Bradford has learned from the best, composed on her own, and developed an impeccable instinct.

The Case Against Versatility: Why Being A Jack-of-All-Trades Dancer Won't Help You

These days, everyone tells you how important it is to be versatile. But what if you're convinced there's just one style that's right for you? It can be tough to balance a deep interest in a single specialty and still meet many choreographers' expectations.

Julia K. Gleich suggests branching out to discover what you don't want. Photo courtesy Brooklyn Ballet

Excerpt:

These days, everyone tells you how important it is to be versatile. But what if you're convinced there's just one style that's right for you? It can be tough to balance a deep interest in a single specialty and still meet many choreographers' expectations. Luckily, you don't have to choose between all in or all over the place, as long as you follow your interests thoughtfully.

Take Time to Find Your Style

When you're young, study a little of everything—that's how you'll figure out what you like to do and where you really shine. No one technique can provide everything you need, says Julia K. Gleich, founder of contemporary ballet company Gleich Dances and a frequent teacher at Peridance Capezio Center. "If you're confined to a single aesthetic, you're missing out on a wider vision of the world that informs your art."

Ask yourself if you're being stubborn about specializing just to stay in your comfort zone. "If you're sticking to a single technique out of fear of the unknown, you're in trouble," says Gleich. Choreographer Al Blackstone agrees: "You may think you know what you want, but allow yourself to be wrong," he says. You may even choose to diversify your training to be sure that your specialty is the style for you. "You need knowledge of other forms to understand your own better and know what you don't want to do," says Gleich. "So if you're convinced you want to pursue Balanchine, take class from a few Cecchetti teachers, too."

How Graffiti Influenced Elizabeth Murray

Given some historical context, the impact graffiti had on the paintings Murray made during the 1980s is plain to see.

The 1980’s were a bodacious, hellacious, and most radical decade. Mötley Crüe got it right titling the era (and their greatest hits compilation album) the, “Decade of Decadence!” Intertwined with the rise of hip hop culture and a myriad international styles riffing off the energy of the streets in Los Angeles and New York City, graffiti exploded onto the scene. Artists in New York City in particular found inspiration in the tags, zips, and murals thrown up in endless rotation on subway cars and the buildings lining city streets.

As New York City slid towards bankruptcy in the mid-‘70s, graffiti, with its expressive, colorful, and vandalistic ways, amplified the voice of a significant subculture. “Only the very rich among New Yorkers could ignore the ubiquity of a new underground visual culture, which seemed to be rising like a red tide to cover public spaces: the spray-can art of the graffiti writers,” wrote curator Kirk Varnedoe in his 1990 essay “High & Low: Modern Art / Popular Culture,” “[Graffiti] suggested a city out of control, in which the most basic premises of civility had been surrendered.” Fierce competitive battles of new street styles covered subways and public spaces, and just at the moment the MTA made the elimination of graffiti a priority in the early ’80s, it was hitting the mainstream art world. Artists that once practiced surreptitiously began showing up in alternative spaces — first in the East Village, and then SoHo and 57th Street. The scene celebrated Keith Haring, Kenny Scharf, and wunderkind Jean-Michel Basquiat.

About the same time, Elizabeth Murray’s reputation was well on the rise. She was counted among a short list of artists credited for resuscitating painting when much of the art world proclaimed painting to be dead. By the late ‘70s she had all but abandoned the traditional rectangular canvas, opting for eccentric, irregularly shaped canvases. The twisting and skewing of her paintings would eventually introduce a three-dimensionality that opened a new space for painting. An important influence we can see in contemporary painters like Ruth Root and Justine Hill.

Although her childhood fascination with comics would remain a major influence throughout her four-decade career, it’s plain to see the impact graffiti had on the paintings Murray made during the ‘80s.

“Popular culture is one part of teeming life that everybody, all of us, are involved in,” Murray told filmmaker Michael Blackwood in 1990, for his film Art in an Age of Mass Culture. She continued:

Whether we know it or not, even if we try to withdraw ourselves from it, we are all really involved in it every day when we walk out into the streets and you hear a … guy walking by with his box blasting a rap song at you. Or in the middle of the subway. Or walking up Broadway. I mean, it’s pouring out at you all the time.

The Untold Story of Rauschenberg’s Earliest Champion

Among the reigning patriarchs of the New York School, the young Rauschenberg found his greatest and earliest champion in the painter Jack Tworkov.

Robert Rauschenberg “Jack Tworkov at the easel” (July, 1952) photo © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Collection of Estate of Jack Tworkov, New York

It is hard to imagine a time when Robert Rauschenberg wasn’t wildly admired. But it certainly was the case in the earliest days of his career, especially among the older generation of Abstract Expressionists who found him irreverent. They labeled his antics “anti-art,” and disregarded him altogether.

Rauschenberg was up against a stigma that dated back to the 1930s, held by artists like Pollock’s mentor, Thomas Hart Benton who believed that intellectuals, Marxists, and homosexuals had overtaken the American art scene. Abstraction equalled immorality in his view.

Yet the young Rauschenberg would find among the reigning patriarchs of the New York School, his greatest and earliest champion in the painter Jack Tworkov who was twenty-five years his senior.

Although drastically differing in temperaments, Tworkov and Rauschenberg both shared a common adversary: hundreds of years of European history, theory, and dominance in the arts. Tworkov and the New York painters of his generation argued from an existentialist platform “[declaring] their independence from all institutionalized concepts of the artist’s role in society,” wrote Dore Ashton. And they placed an importance on the individual over all else. “Painting is self-discovery,” Pollock told Selden Rodman in 1956, “Every good artist paints what he is.” Rauschenberg took this notion and ran with it.

Tworkov first became acquainted with Rauschenberg in the milieu of downtown New York. The journals of Tworkov, the letters of Rauschenberg, and two revelatory books by Calvin Tompkins, The Bride and the Bachelors (1965) and Off the Wall: Robert Rauschenberg and the art world of our time (1980) reveal the depth of their relatively unknown friendship.

An Ambitious Survey of the Titans of Abstract Expressionism

This expansive AbEx show is brash, irreverent, and unconstrained, just like the period it aims to express.

Jackson Pollock, “Blue Poles” (1952), enamel and aluminium paint with glass on canvas, 212.1 x 488.9 cm, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra (© The Pollock-Krasner Foundation ARS, NY and DACS, London 2016)

The titans of Abstract Expressionism are on view now at The Royal Academy of Arts in London. It’s a massive show comprising 163 works by 30 painters, sculptors, and photographers, and will likely go down in history as the largest loan exhibition of its kind.

It’s been close to 60 years since a show like this has been held on European soil (“New American Painting” toured eight European cities including the Tate, London, in 1958). The 12 colossal Beaux-Arts galleries can barely accommodate this explosive and ambitious survey of the prevailing personalities and perspectives associated with America’s greatest art movement. Curated by David Anfam, the movement’s leading expert, the show is brash, irreverent, and unconstrained, just like the period it aims to express. (For a tame chronological recap of the exhibition, buy the equally impressive publication that accompanies the show).

Never has a generation of avant-garde artists been more revered than those central to the Abstract Expressionist movement in America. Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, Barnett Newman, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still, and their counterparts Adolph Gottlieb, Philip Guston, Robert Motherwell, Ad Reinhardt, David Smith, and Jack Tworkov made history with their gestural works celebrating existentialism and raw humanity. It is their works that reign supreme in the show. Bonding through their time together on the WPA in the 30s and the comradery of The Club in the 50s, these artists made New York City the new capital of the art world with their new art.

Abstract Expressionism marked the first time in history that pure abstract art would rival old Modernism. “It was the moment when New York artists suddenly achieved self-awareness,” wrote the critic Thomas B. Hess in a profile about the scene for New York Magazine in December 1974, “realizing that they were together, and together could move ahead independently of a suffocating Paris-based aesthetic, which had dominated international markets of ideas and cash for over 150 years.”

She’s Sayin'

Gleich writes about her experience meeting and observing Annabelle Lopez-Ochoa while she created “Broken Wings” for English National Ballet’s “She Said” all-female triple bill. Gleich’s Choreographer Observership was awarded by OneDanceUK.

Gleich writes about her experience meeting and observing Annabelle Lopez-Ochoa while she created “Broken Wings” for English National Ballet’s “She Said” all-female triple bill. Gleich’s Choreographer Observership was awarded by OneDanceUK.

A Designer Experiments with Digital Design, After 60 Years of Handcrafted Furniture

This expansive AbEx show is brash, irreverent, and unconstrained, just like the period it aims to express.

Wendell Castle, “Table-Chair-Stool” (1968) with “Serpentine Floor Lamp” (1965–67), installation view in ‘Wendell Castle Remastered’ at the Museum of Arts and Design, New York (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Designer Wendell Castle has made a career out of challenging the boundaries that define art and furniture. A new exhibition, Wendell Castle Remastered, on view at the Museum of Arts and Design, celebrates Castle’s many innovations, juxtaposing a selection of historically significant works against a group of new works that combine handcraftsmanship and digital technologies, including 3D scanning, 3D modeling, and computer-controlled milling. This is the first exhibition to examine Castle’s digitally crafted works.

While his predecessors, like George Nakashima, preferred the organic expressiveness of the surface of wood, Castle developed a sculptural technique in the early 1960s called “stack lamination,” where thick slabs of wood were glued together before being carved into dynamic biomorphic shapes. It was this unprecedented approach to furniture-making that has defined Castle’s six-decade career and made him a legend in the American art furniture movement.

“Scribe’s Stool” (1961–62) is one of the earliest works on view. Tall, thin, sinewy, and boney, the stool seems technically functional, yet its ungainly highchair-like structure would make sitting on it difficult. The elaborate, sweeping gestures of Art Nouveau were an obvious inspiration for this and other early works on view. “Scribe’s Stool,” above all, emphasizes Castle’s evolving wish that his furniture be thought of and collected on the same terms as sculpture.

“Blanket Chest” (1963) is Castle’s first stack-laminated cabinet. It’s a voluptuous, radish-shaped work — and a prelude, as Castle would soon master this technique, giving him the ability to realize even larger and more texturally animated, voluminous designs that recall the biomorphic works of Jean Arp and Henry Moore.

Castle’s “Serpentine Floor Lamp” (1965–67) seems unabashedly designed for the marketplace. It’s an elegant work in mahogany, that curves and bends and straightens itself. The work was actually the result of Castle manipulating and twisting a paper clip.

Minimalist Duets in Sculpture and Dance

This expansive AbEx show is brash, irreverent, and unconstrained, just like the period it aims to express.

Yvonne Rainer’s ‘Connecticut Rehearsal’ (1969) and Ronald Bladen’s “Cosmic Seed” (1977) (click to enlarge)

During the summer of 1960, dance artists Simone Forti, Nancy Meehan, and Yvonne Rainer rented rehearsal space at Dance Players on Sixth Avenue so they could improvise together. Sitting in on a rehearsal, the-soon-to-be-sculptor Robert Morris — who was married to Forti at the time — commented that the best moments were when they weren’t dancing.

So began the conversations among a historic group of dance makers that would grow to include Trisha Brown, Steve Paxton, Deborah and Alex Hay, and others, all of whom would make up the Judson Dance Theater. Their work broke with tradition and embraced movement based on process, improvisation, and causality. It represented not a single prevailing aesthetic but rather an effort to “preserve an ambiance of diversity and freedom,” wrote dance historian Sally Banes.

Seemingly simultaneously, sculptors like Morris, Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, George Sugarman, Tony Smith, and Anne Truitt also moved away from tradition in their field, abandoning the practice of modeling and carving and embracing a new kind of artistic autonomy — one which emphasized the clarity of the constructed object as well as the space created by it. Their manufactured and fabricated work came to be called minimalism.

Where Sculpture and Dance Meet: Minimalism from 1961 to 1979 is an exhibition at the Loretta Howard Gallery that explores this overlap. Curated by dancer–turned–dance critic Wendy Perron in collaboration with historian Julie Martin, the show pairs videos of historic performances of dances by Merce Cunningham, Lucinda Childs, Trisha Brown, Simone Forti, Yvonne Rainer, and (surprisingly) Robert Morris, with sculptures by Ronald Bladen, Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, Morris, and Andy Warhol, exploring the dialogue surrounding concurrent ideas of minimalism in dance, performance, and art.

“The label minimalist is a handy way of calling attention to a basic approach to composition,” wrote dance critic Jack Anderson in 1987 in the New York Times. I imagine the curators of the exhibition had Anderson’s handy approach in mind as they set about juxtaposing dance makers and sculptors from this historic period in American art.

But lumping a group of artists together as “minimalists” ignores how different they are from one another and simplifies the intentions behind their art. Dance makers during this time may have used movement sparingly and without embellishment, but that doesn’t mean they shared the same severity as, say, Donald Judd (and we know how much he rejected the minimalist label). Both Judd and Morris denied that their objects related to architecture, technology, or mathematics; instead, they emphasized their occupation with formal problems, with the “autonomous and literal nature of sculpture,” as Morris put it. Aptly for this show, their approach can be summed up by a statement from Yvonne Rainer: “In the studio, I work with aesthetics like a shoemaker works with leather.”

“Illuminations” in SDHS Conversations Across the Field of Dance Studies: Network of Pointes, Volume XXXV

I trained in NYC in the heyday of ballet, in the 1970s, when New York was a dance world capital. A student of Melissa Hayden, I studied with David Howard, Robert Denvers, Willie Berman, and many others.

Photo: Jason Andrew

I trained in NYC in the heyday of ballet, in the 1970s, when New York was a dance world capital. A student of Melissa Hayden, I studied with David Howard, Robert Denvers, Willie Berman, and many others. In briefly attending the School of American Ballet, I was in class with dancers from NYCB and ABT, defectors from Russia, and the energy was inspiring and thrilling. For me, ballet was just ballet. It was Balanchine and Petipa, Robbins and Joffrey, Tharp and De Mille. Those were also the days of the Joffrey company in NYC and they had a strong influence on my attitude toward ballet with a somewhat inclusive company model dancers of different shapes, sizes, and colors, and a varied repertory that included ballet to rock music. In hindsight, I was embracing a contemporary aesthetic, but was in class all the time with "ballet" dancers. Rarely do I remember being mired in a singular style or sticking to narrow, rigid, classical ideals. But I never would have called our dancing contemporary, nor would I have called it classical. It was simply ballet.

Two decades later, while teaching and choreographing in New York City in the 1990s, participated in a ballet choreography master class. At the time I identified with ballet as my medium, but upon showing my first study it was suggested that what I had made was "not ballet" but "something more modern like Graham or Cunningham." Naturally I responded with great pleasure and said, "yes, it's like 'me'!" The master teacher was not impressed by my response and left me to ponder why I was taking the workshop in the first place. I thought I knew why: I came from ballet and used pointe work. My dancers were usually ballet trained and I felt I had not immersed myself in modern approaches to creativity. But what I produced seemed not “ballet enough.”

This furthered questions about my identity as a choreographer, teacher, and dancer. For my next project in 1999 I hired dancers from a program that was focused on modern dance. The piece was on pointe and quickly realized there were unique differences in these dancers. They were less vertical, but also less daring en pointe and philosophically burdened by a need to solidify a modern identity within the piece. This experience influenced my approach to teach ballet, especially at the higher education level. What I wanted for my students was reflected in a technique that was neither of the ballet or the modern/contemporary extremes, but based in movement invention utilizing a ballet vocabulary. Choreographically, want what is valued in both the modern and ballet worlds (or contemporary and classical?). Today I choose to work with ballet dancers who are strong on pointe and open to new methods. And teach dancers to be hireable. We don't know what new idea is going to capture the imagination of dance audiences next.

The Brute Classicism of Joel Perlman

Partial gallery view, Joel Perlman at Loretta Howard Gallery (all photographs by the author for Hyperallergic)

It’s been over twenty years since we’ve seen Joel Perlman’s large-scale sculptures on exhibition in New York City. The size and weight of his mighty works in welded steel can be a challenge to show, but Loretta Howard Gallery has pulled out all the stops with its current exhibition, bringing in five new large-scale works (four in welded steel and one in aluminum). The show also includes a small work in weathered steel, a hanging cast bronze, and a wall-mounted work in aluminum.

For much of the last forty years, Perlman has been creating towering sentinels in steel. His process has remained relatively unchanged since the very beginning: snapping huge industrial-grade planes of steel together with bold welds using a torch and his bare hands. Perlman is a stand-alone original preceded by Anthony Caro and David Smith.

Contemporary sculpture today can be defined by two extremes. One rooted in multiple points of reference as in the work of Paul McCarthy, which employs a mixed use of materials and crosses mediums where even the exhibition space can be appropriated as part of the ‘medium.’ The other rooted in singularity like the work of Richard Serra, whose massive large-scale works are specific to a direct exchange with the artwork. The first accentuates the artist’s strategy as a retort or response to an external societal change in the world. The second articulates the ambition of the individual through an attention to trueness in form and materials. The work of Joel Perlman belongs to the latter.

Perlman learned to weld alongside mechanics, farmers and trucker drivers at a night class offered at Ames Welding in downtown Ithaca while he was an undergraduate at Cornell University in the early 1960s. Welding was like “magic,” Perlman recalls, “You touch a rod to metal, there’s a flash and buzz, and two pieces become one.”

After the Miami Art Fairs: 9 Artists to Watch

MIAMI BEACH — One of the most exciting aspects of the art market is the discovery of new talent. In the early 1950s Ivan Karp and Leo Castelli marched down to derelict Fulton Street to meet up with the young Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. Not much later, historic figures like Holly Solomon and Paula Cooper climbed flight after flight of stairs navigating the cold-water flats of downtown to make their discoveries.

You never know what you’ll find at an art fair, like this corner of Cameron Gray’s installation at the Mike Weiss Gallery at Art Miami. (photograph by Hrag Vartanian for Hyperallergic)

MIAMI BEACH — One of the most exciting aspects of the art market is the discovery of new talent. In the early 1950s Ivan Karp and Leo Castelli marched down to derelict Fulton Street to meet up with the young Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. Not much later, historic figures like Holly Solomon and Paula Cooper climbed flight after flight of stairs navigating the cold-water flats of downtown to make their discoveries.

Today, the art fairs have become a nexus for “discovery.” Collectors, and moreover their art consultants, have come to rely almost solely on them. With hundreds upon hundreds of galleries and dealers descending upon the United States’s largest art fair last week, it can seem daunting to find that diamond of an artist in the rough that is Miami. Booth after booth and fairs upon fairs, how can anyone make scene of it all?

Discovering talent is a talent itself. As often is the case, experience and perseverance are key. Having followed the careers of hundreds of artists, it was excited to see a few making their Miami debut. Many of the artists I have selected here I have been following for a number of years, and it’s great to see them break out in Miami.

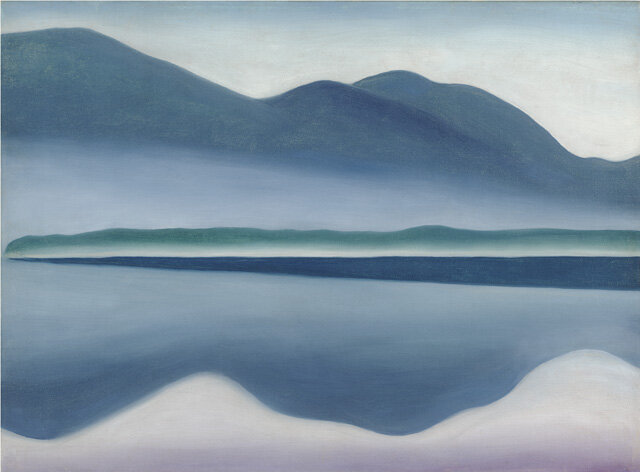

A Painter’s Retreat: Georgia O’Keeffe and Lake George

MIAMI BEACH — One of the most exciting aspects of the art market is the discovery of new talent. In the early 1950s Ivan Karp and Leo Castelli marched down to derelict Fulton Street to meet up with the young Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. Not much later, historic figures like Holly Solomon and Paula Cooper climbed flight after flight of stairs navigating the cold-water flats of downtown to make their discoveries.

Lake George, 1922, oil on canvas, 16 ¼ x 22 in., San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Gift of Charlotte Mack (image © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York)

Glen Falls, NY — An ambitious exhibition on view this summer at the Hyde Collection is the first of its kind to explore the formative influence of Lake George on the art and life of Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986). O’Keeffe, the great Maiden of American Modernism, is celebrated most for the existential paintings she created out in the dry air of New Mexico, but as this exhibition attests, the works painted on the shore and in the hills around New York’s Lake George are among the most prolific and transformative of her seven-decade career.

The Hyde Collection is an extraordinary place, one of the few of its kind in upstate New York. A product of the golden age of the private art collector, it’s a prime example of the rare genre of museums created during the American Renaissance. Turned into a public museum by Charlotte Pruyn Hyde in 1952, she dedicated her estate and art collection to the community. Her two story house — the Hyde House — was constructed between 1910 and 1912 in the style of an Italian Renaissance palazzo and architecturally inspired by the Isabella Stewart Gardner’s Fenway Court in Boston.

The collection within consists of over 3,330 objects that span the history of Western art from Old Masters such as Sandro Botticelli, Rembrandt, Peter Paul Rubens, and El Greco’s “Portrait of St. James the Less” to modern masters such as Matisse and blue period Picasso in Mrs. Hyde’s Bedroom. The Hyde also contains a fine assortment of American art, with works by George Bellows, Thomas Eakins, Winslow Homer and — my favorite discovery — an Arthur B. Davies painting of Salt Lake, Utah, hanging in the Down Guest Bedroom. The O’Keeffe exhibition is located in the Woodward Gallery a modern building located adjacent to the Hyde House. It’s a fitting venue for an intimate look at O’Keeffe.

Modern Nature: Georgia O’Keeffe and Lake George offers sixty paintings dating from 1918-1934. Curated by Erin B. Coe (Chief Curator at the Hyde), and Barbara Buhler Lynes (former curator of the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum), the exhibit is divided into six themes: Landscapes, Barns and Buildings, Abstractions, Tree Portraits, From the Garden, and Lake George Souvenirs. The exhibition also includes significant loans from dozens of major collecting institutions from across the United States and is quite a coup for the Hyde.

America’s Grand Gestures Reign Supreme Again in Basel

Fifty-five years ago, the exhibition The New American Painting arrived at the Kunsthalle Basel. It was the first stop on a yearlong tour that touted the work of seventeen Abstract Expressionists before eight European countries — the first comprehensive exhibition to be sent to Europe showing the advanced tendencies in American painting.

Franz Kline’s “Provincetown II” (1959), oil on canvas, 93 x 79 in, heralds the return of postwar American painting at Art Basel. (image courtesy Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York)

BASEL, Switzerland — Fifty-five years ago, the exhibition The New American Painting arrived at the Kunsthalle Basel. It was the first stop on a yearlong tour that touted the work of seventeen Abstract Expressionists before eight European countries — the first comprehensive exhibition to be sent to Europe showing the advanced tendencies in American painting. Organized by the International Program of the Museum of Modern Art under the auspices of the International Council at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, the show was curated by Dorothy Miller and featured William Baziotes, James Brooks, Sam Francis, Arshile Gorky, Adolph Gottlieb, Philip Guston, Grace Hartigan, Franz Kline, Willem de Kooning, Robert Motherwell, Barnett Newman, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Theodoros Stamos, Clyfford Still, Bradley Walker Tomlin, and Jack Tworkov.

Director of MoMA at the time Alfred H. Barr, Jr. explained in a press release for the show that the artists in The New American Painting represented an individual liberty of style and expression. “None speaks for the others any more than he paints for the others,” he said. “Their individualism is uncompromising and as a matter of principle they do nothing deliberate in their work to make communication easy.”

The exhibition opened at the height of the Cold War, and for years it was rumored that it was all part of a secret CIA program aimed at promoting American ideals abroad — ideals that would later include the marketing of fast food and Walt Disney. The connection seemed improbable; after all, this was a period when the great majority of Americans disliked or even despised modern art. Even President Truman validated the popular view when he said: “If that’s art, then I’m a Hottentot.” However, the CIA connection was confirmed in a 1995 article published in the Independent.

Much time and history have passed since the heroic showing of The New American Painting. By the early 1960s, Pop art had surpassed Abstract Expression, and by the late 1960s, Minimalism and then Conceptual art had buried it. Today most of the art market still hedges its bets on contemporary art. So I was astonished to see postwar American painting and sculpture dominating the halls of the 44th edition of Art Basel. Could this be a response to the record sales recently recorded by New American Painting alums Barnett Newman and Jackson Pollock?

At Sotheby’s last month, Barnett Newman’s seminal painting “Onement VI,” a deep blue abstract composition from 1953, sold for $43.8 million, the result of a battle among five bidders. The price eclipsed Newman’s previous auction record by a margin of more than $20 million. The monumental 1953 painting was championed as one of the most important works by the artist ever to appear at auction and stands as a masterwork not only of Newman’s artistic enterprise, but of the entire Abstract Expressionist movement.

Black Mountain College Veteran’s Curiosity Spurs Her Art

The brilliant and inventive mind of Susan Weil is on full display at the Sundaram Tagore Gallery through June 15. At 83, Weil has lived at the epicenter of the New York art world since the early 1950s, and although her art has been relatively overshadowed by that of her contemporaries, Weil’s current show has the makings of her best.

“Susan Weil: Time’s Pace,” installation view at Sundaram Tagore Gallery, with “Georgia” (2013), left, and “Perspectacle” (2013), right (all photos by the author for Hyperallergic unless otherwise noted)

The brilliant and inventive mind of Susan Weil is on full display at the Sundaram Tagore Gallery through June 15. At 83, Weil has lived at the epicenter of the New York art world since the early 1950s, and although her art has been relatively overshadowed by that of her contemporaries, Weil’s current show has the makings of her best.

Weil was born in New York City in 1930 and grew up on Outer Island, NY. She came of age as an artist just as the postwar New York School was gaining steam. While attending the Académie Julian in Paris in 1948, she met Robert Rauschenberg, and for a time they became an inseparable pair. He followed her to Black Mountain College, both studying under Josef Albers. “I was still a teenager at Black Mountain,” Weil said in an interview years ago. “I had a defensive response to Albers’s authoritarian, exacting style. And yet I can see how his teachings have influenced me to this day.” Rauschenberg and Weil returned to New York and began participating in the extraordinary art scene of the time. “The interdisciplinary collaborations that we had enjoyed at Black Mountain were also blossoming in New York with events that combined dance, photography, and music,” Weil said. “Fences separating different disciplines came down.” Rauschenberg and Weil shared their thoughts and work with de Kooning, Kline, Tworkov, and others.

The pair spent the summer of 1949 on Outer Island. They bought a roll of blueprint paper and began staging compositions, exposing the paper to sunlight (Weil had experimented with cyanotypes since she was a child). The results of the collaboration were “thrilling,” according to the artist — Bonwit Teller used them in their department store windows; Life magazine published them in an article in April 1951; and the next month one was shown in the exhibition Abstraction in Photography at the Museum of Modern Art.

The Emotive Musculature of Resurrection

Stephen Petronio has been a creative force in the dance world for nearly 30 years. The most compelling aspect of Petronio’s career, and most intriguing for me, is his desire to collaborate, inviting composers, musicians, and visual artists to take on an idea and expand it within and beyond the dance.

Stephen Petronio (left) and artist Janine Antoni (right) set the scene as the audience takes their seats for “Like Lazarus Did” the new performance by Stephen Petronio Company (photograph by the author for Hyperallergic)

Stephen Petronio has been a creative force in the dance world for nearly 30 years. The most compelling aspect of Petronio’s career, and most intriguing for me, is his desire to collaborate, inviting composers, musicians, and visual artists to take on an idea and expand it within and beyond the dance.

For his current season at the Joyce, Petronio offers “Like Lazarus Did,” and with it heavy ideas of reincarnation and resurrection. His collaborators include composer Son Lux performing live with members of yMusic and The Young People’s Chorus of New York City, artist Janine Antoni, whose primary tool for sculpture has always been her own body, lighting by Ken Tabachnick, and costumes by H. Petal and Tara Subkoff.

I haven’t seen enough Petornio to say that I’m an expert. I approached the work as one obsessed with cross-disciplinary collaboration and with high expectations for the roles various art forms can play within a single production.

“Lazarus’ resurrection, the phoenix rising, and cycles of reincarnation are compelling ideas,” Petronio offers in his program notes, but getting across such heroic concepts can be a challenge even for the seasoned Petorino.

This isn’t Petronio’s first foray into the subject matter of death. Nearly 10 years ago his company presented “The King is Dead (Part I)” featuring stage design by Cindy Sherman, including slide projections showing mummified body parts with costumes by Manolo. A press release asserted that the dance concerns “the symbolic death of the male figure.”

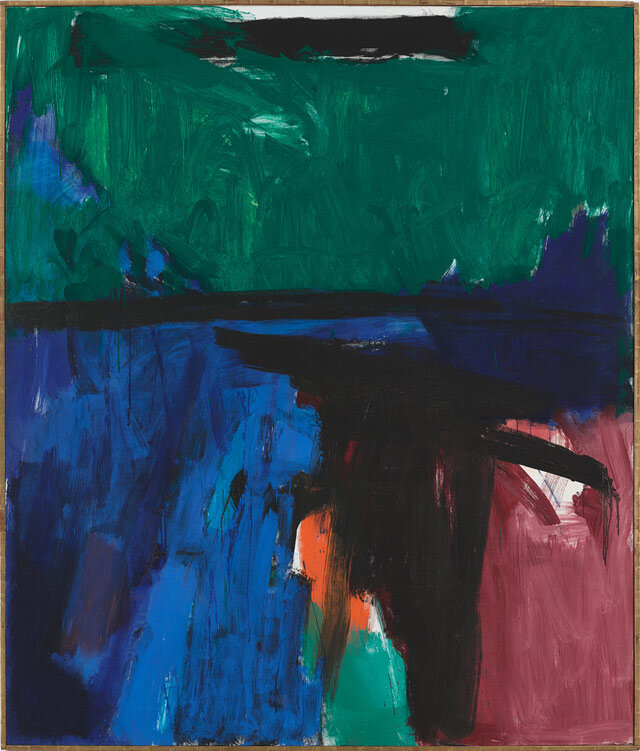

A Blood on the Moon Fierceness: Fritz Bultman’s Paintings and Collages

“Painting deals with paradox,” wrote the artist Fritz Bultman in a notebook he titled Time and Nature, “For paradox offers us a tantalizing choice that is purely human and it is as a human document, not as a stylistic development, that art has a reason for existence.”

Fritz Blutman, “Rosa Park” ( 1958) (All images courtesy Estate of Fritz Bultman and Edelman Arts, New York)

“Painting deals with paradox,” wrote the artist Fritz Bultman in a notebook he titled Time and Nature, “For paradox offers us a tantalizing choice that is purely human and it is as a human document, not as a stylistic development, that art has a reason for existence.”

For Bultman, who unfortunately missed his photo-op as one of “The Irascibles” (the group of Abstract Expressionist painters made famous by a 1951 photograph in Life magazine), the paradox in painting was bridging nature and art. On view now at Edelman Arts is an exhibition of some of Bultman’s most important work, offering a rare opportunity to experience the artist’s struggle with this elusive paradox. The exhibition marks the first exhibition of Bultman’s work held in New York in nearly a decade. (The last exhibition was held in 2004 at Gallery Schlesinger, Bultman’s primary advocate since 1982.)

Fritz Bultman (1919–1985) was among the artists associated with the first generation of the New York School. He split his time between Provincetown and New York and counted among his close friends icons like Hans Hoffman, Lee Krasner, Stanley Kunitz, Robert Motherwell, Jackson Pollock, Tony Smith, and Jack Tworkov.

In 1950, Bultman signed the historic letter protesting the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s indifference to Abstract Expressionism and other forms of advanced art. Labeled by the press as “The Irascibles,” the group included almost all the artists who would achieve international acclaim as Abstract Expressionists. Unfortunately Bultman was studying sculpture in Italy at the time and missed the photo shoot for Nina Leen’s famous photograph, published in the January 15, 1951 issue of Life magazine. His absence from the iconic group portrait undoubtedly denied him a more prominent place in the history of post-war American art. Robert Motherwell proclaimed that of all the painters of his generation, Bultman was “the one [most] drastically and shockingly underrated.”

Less Is More at the Armory Show Modern

Let’s face it: navigating Armory Week and all its various satellites is a bitch. With so much art to see and endless booths to maneuver, it’s all very daunting. But we love it. Well, at least I love it.

Jean-Paul Riopelle, “Untitled (Iceberg Series)” (1977), oil on canvas, 10 3/5 × 13 4/5 in (courtesy Oriol Galería d’Art)

Let’s face it: navigating Armory Week and all its various satellites is a bitch. With so much art to see and endless booths to maneuver, it’s all very daunting. But we love it. Well, at least I love it.

Spontaneity and taxis are the two things I rely on the most. Spontaneity, because one should always open to possibilities, no matter what the schedule might dictate. Taxis, because who in their right mind wants to walk the five long-ass blocks to Pier 92, where the Armory Show’s Modern section was housed, from the subway (with a headwind off the Hudson River that somehow affects travel in both directions)?

A tiny black-and-white painting by the expressionist Jean-Paul Riopelle, “Untitled (Iceberg Series)” (1977), was the first work that grabbed me. On view at the booth of Oriol Galería d’Art, based in Barcelona, the painting measures only 10 by 13 inches but is incredibly seductive. Riopelle was known for his voluminous impasto, and this little work does not disappoint, with heavy lines of black carved deep into the back of the canvas with palette knife. Its simplistic, totemic gestures echo a range of history painting that could easily date back to the Lascaux caves. In 1972, Riopelle returned to his hometown of Québec and built a studio at Sainte-Marguerite-du-Lac-Masson. The stark northern landscapes there inspired his Iceberg Series of 1977 and 1978, to which this painting is attributed.

The Painterly Cravings of Larry Poons

Larry Poons might be considered one of the top painters working today, and he knows it. Over his five-decade career he has painted seminal works that have been shown and owned by an illustrious list of prominent private and museum collections all over the world.

Larry Poons, “Giordano Bruno” (2011) and “Untitled (012D-5)” (2012) (Image courtesy Jason Andrew)

Larry Poons might be considered one of the top painters working today, and he knows it. Over his five-decade career he has painted seminal works that have been shown and owned by an illustrious list of prominent private and museum collections all over the world. Critics and historians have written about his work for decades, with pages upon pages chronicling his modes and methods.

With so much history behind him, and considering that the artist is reaching nearly 80 years old, one might anticipate a lull in his creative output. But Poons remains one of our greatest painters. Like Mario Andretti lives for speed, Poons craves after paint. An exhibition of his most recent work, organized in tandem by the Loretta Howard Gallery and Danese gallery, is chock-full of the best painting on view in New York. Can you tell I’m a fan?

Poons’s work is about color. It’s been about color since his history-making dot paintings of the ’60s. And it’s been about color since his vigorous throw paintings of the ’70s. In the ’80s and ’90s, as surface and texture became prominent in his work, color, while it may seem to have taken a back seat to the physicality of the painting, still remained constant. And in recent years we’ve seen a welcome return to the brush.

“The Flying Blue Cat,” “Tycho Brahe,” and “Barreling” have expansive landscaped horizons and color staccatoed across the canvas in an all-over rhythm. They and the others in the show allude to a narrative but offer no wholly recognizable forms. Maelstroms of line and color tell a story more complicated than your typical “Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte.” But Poons isn’t a history painter by any means. “Spend some time with them,” he tells me. “It’s about the eye; it’s always been about the eye.”