Resources

ABOUT US / SERVICES / OUR CLIENTS / STORE / CONTACT

Tech Start-Up Aims to Get Artists Royalties for Resale

Fairchain generates digital contracts and certificates of title and authenticity, allowing artists to track their work and share in secondary market proceeds.

Even before the artist Robert Rauschenberg famously objected to seeing a 1958 painting he originally sold for $900 flip for $85,000 in 1973, artists have been frustrated by not receiving royalties for their work when it changes hands.

Previous efforts to address this over the years have failed. But now, as musicians and other creative producers assert more control over their future sales and blockchain technology has allowed for easier tracking of intellectual property, two Stanford alumni have started a business to help visual artists reap the financial rewards when their work is resold privately or comes up for auction, in some cases at many multiples of the original price.

“There has been exponential growth in the secondary market, but artists have largely been left behind, even though they are essential to it,” Max Kendrick, one of the founders, said. “How do we create a more sustainable model for the artist and the galleries that support them?”

Charlie Jarvis, 24, a computer scientist, and Kendrick, 36, a former diplomat and a son of the sculptor Mel Kendrick, started the company, called Fairchain, in 2019. Little by little, it is gaining traction with artists and gallerists.

New York’s Midcentury Art Scene Springs to Life in ‘The Loft Generation’

Edith Schloss's memoir recounts an era of great creative vitality and the time she spent with Willem and Elaine de Kooning, Merce Cunningham

Many prophesied the demise of New York City during the Great and Temporary Exodus of 2020. But none had quite the dramatic vision of Jack Tworkov, the abstract expressionist painter, in the middle of the previous century. “Imagine a great catastrophe. And all this mowed down,” he mused then, looking at photographs of buildings, envisioning rust and dust. “And tourists wandering around in all that emptiness — where was the Flatiron, the Empire State — looking for past grandeur. Imagine good old New York someday just like Egypt.”

Tworkov is one of scores who come bearing aperçus in the German American writer and artist Edith Schloss’s memoir, “The Loft Generation,” discovered in rough-draft form after her death in 2011. It’s been polished into a glowing jewel of a book by several editors including Mary Venturini, who worked with her in later years at a magazine for expats in Rome, and Schloss’s son, Jacob Burckhardt.

Ron Gorchov, Painter Who Challenged Viewers’ Perceptions, Dies at 90

Seeking “a new kind of visual space” and using a vivid palette, he stacked multiple canvases with gently curved, round-cornered tops.

Ron Gorchov at his studio in Brooklyn in 2012. Dissatisfied with painting on a flat rectilinear surface, he began creating pieces that were saddle-shaped. Credit: Brian Buckley

Ron Gorchov, an abstract painter known for vividly colored, saddle-shaped canvases that curved away from the wall and gently warped the viewer’s perception, died on Aug. 18 at his home in Red Hook, Brooklyn. He was 90.

His death was confirmed by his Manhattan gallery, Cheim & Read. His family said the cause was lung cancer.

A tall, solidly built man with a kindly face, Mr. Gorchov may have been the closest thing the New York art world had to a gentle giant in the late 20th century. He was soft-spoken and approachable, with a relaxed manner. In a 2006 interview with The Brooklyn Rail, an art newspaper, he said that his paintings came not from angst but from “reverie, and luck” and “out of leisure.” He attracted a wide following among younger painters, particularly in the last 15 years of his life, when his work enjoyed a new prominence.

Mr. Gorchov was one of many painters who, in the 1970s, ignored rumors of the medium’s death while rejecting the scale, slickness and purity of Minimalist abstraction. These artists personalized abstract painting in all sorts of ways, for instance by adding images, working small or using quirky geometry. Several, including Ralph Humphrey, Robert Mangold, Richard Tuttle, Elizabeth Murray, John Torreano, Lynda Benglis, Marilyn Lenkowsky and Guy Goodwin, put an idiosyncratic, intuitive spin on a Minimalist staple — the shaped canvas. Mr. Gorchov did, too. But he was older, and his art blended some of the grandeur of 1950s Abstract Expressionism with the more skeptical, humorous attitudes of the ’70s.

Maurice Ronald Gorchov was born on April 15, 1930, in Chicago to Herman Noah and Grace (Bloomfield) Gorchov. His father was an entrepreneur. His mother was an artist who had studied painting at the Art Institute of Chicago and who, “began to give me ideas about art pretty early” he said in an unpublished 2017 interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist, artistic director of the Serpentine Galleries in London.

When he was 14, Mr. Gorchov began taking Saturday art classes at the Art Institute. In 1946 and 1947 he took night classes there. When he was 15 he began working as a lifeguard, his 6-foot-4 frame enabling him to pass for 18, the required age. At 18, he decided to become a painter.

Avedon, Unsigned

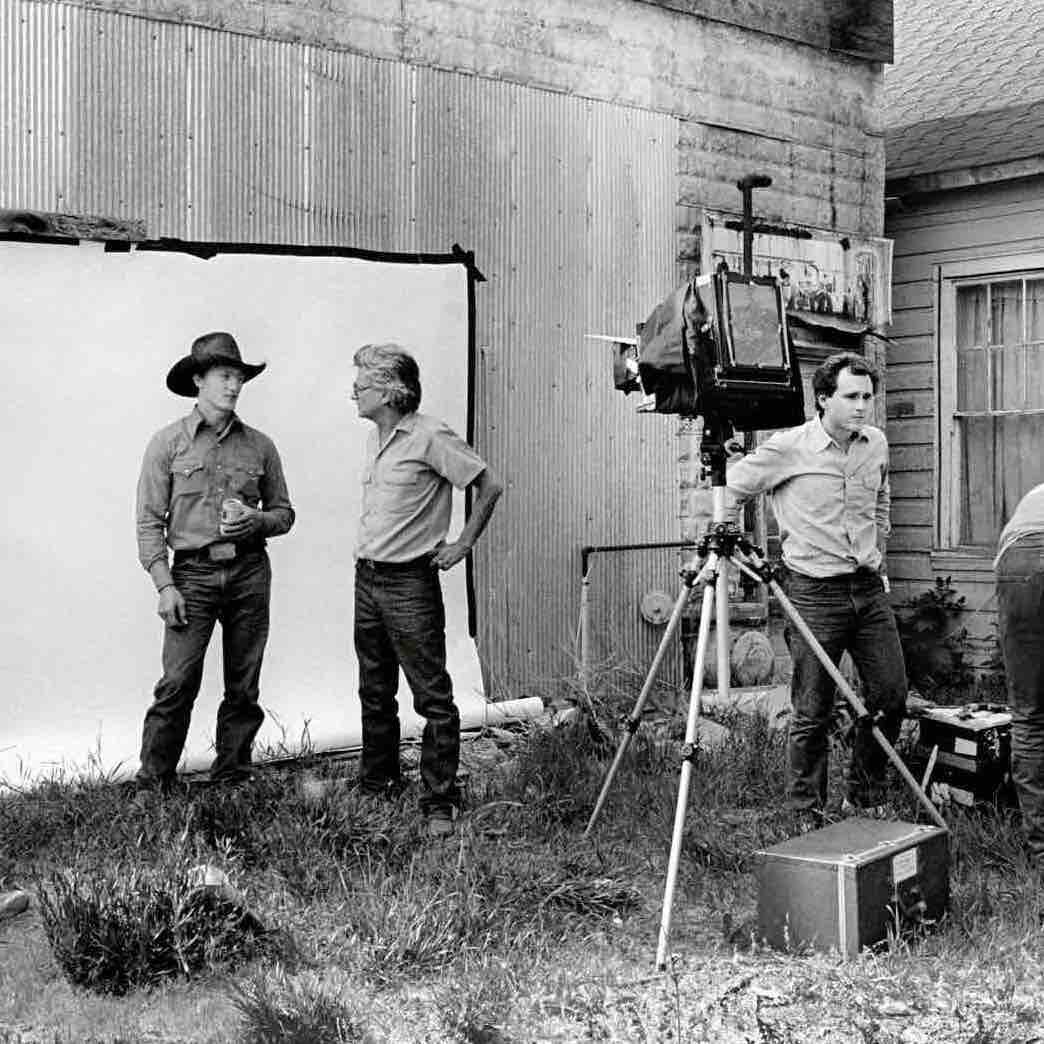

Ruedi Hofmann, master printer for the photographer’s magnum opus, “In the American West,” understood that his payment would be a set of signed prints. He has the prints, but they were never signed. Whose prints are they, anyway?

By Richard B. Woodward

Hanging in the foyer of Ruedi and Ann Hofmann’s art-filled home in Newburgh is a large black-and-white photograph by Richard Avedon.

Unsettling in scale as well as content, it’s a half-length portrait, larger than life-size, of a curly-haired teenage boy who stands against a white background holding up the sagging skin and shiny entrails of an eviscerated rattlesnake. The headless animal’s dark blood is spattered across the bib of his overalls; its curdlike guts squish through the fingers on his right hand. The boy’s hieratic gesture is like that of someone performing an ancient sacrifice, and his hard gaze suggests he has been doing this for much of his young life.

Not many would choose such an image to welcome visitors. Mr. Hofmann is clearly proud of it, though, and more than 100 others like it.

As master printer on Avedon’s last major project, “In the American West,” Mr. Hofmann was responsible for bringing out the myriad gray shades and material details in “Boyd Fortin,” the portrait of the 13-year-old rattlesnake skinner, and the other images of weathered, hard-bitten characters featured in the landmark 1985 exhibition and book.