Review (via Two Coats of Paint): Janice Biala’s epochal studio

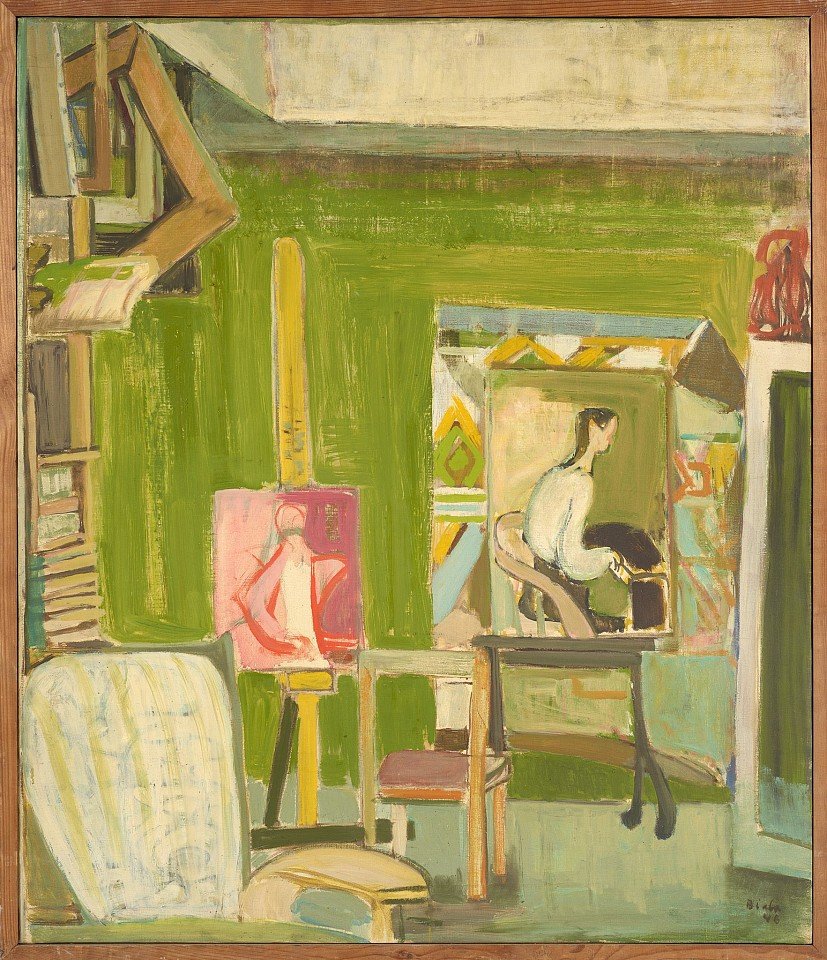

Janice Biala, The Studio, 1946, oil on canvas, 39 1/2 x 22 1/2 inches

by Jonathan Stevenson

A striking feature of the paintings and works on paper of Janice Biala (1903–2000), now on view at Berry Campbell in a show craftily curated by Jason Andrew, is their seamless reconciliation of civilizational clutter and spatial order. Fixing that notion is the earliest painting, The Studio (1946), arraying the artist’s active workspace and establishing her intent to embrace the world through it. (Coincidentally, Vera Iliatova’s “The Drawing Room” at Nathalie Karg gamely recaptures and updates kindred impulses.) Biala’s work here, spanning the immediate postwar period almost to the end of the Cold War and blending the New York School and the School of Paris – she lived in both cities – also bears the considerable weight of twentieth-century history, art and otherwise, with extraordinary grace and weightless cohesion, free of the strain of obvious contrivance.

Façade Blanche (White Facade), painted in 1948, depicts the physical strata of a Paris neighborhood with both due attention to detail and variegation and an implicit emphasis on the calmly agreeable organization of the visible environment, which is pointedly unoccupied. When Biala goes inside, as with Nature Morte à la Table (1948) and White Still Life (1951), she apprehends the material incidents of private life from a distinct remove, according them equal perspectival weight in cool tones that impart a sense of secure refuge within humanity’s sprawl and struggle. Even figures are absorbed into their inanimate surroundings. Jeune fille en rose, assise (Young girl in pink, sitting) is a moderate example, Two Young Girls (Hermine and Helen) a more extreme one verging on abstraction. The idea, it seems, is not the world’s erasure or engulfment but rather its harmonious accommodation of individuals, whatever their identities.

The trappings of Biala’s work are bohemian, not bourgeois, and it has a proletarian undercurrent. In Chevet de Notre Dame et l’ile St. Louis, 1949, the iconic church is iconoclastically painted from the rear, now a passive source of cultural comfort rather than an imposing summoning of faith or awe. Le Louvre (1948) is similarly down-to-earth, spied from the vantage of the Left Bank and settling humbly on the museum’s rooftop. Perhaps unsurprisingly, pieces from the mid to late 1950s, especially collages – see Violincelliste, Blue Parrot, and Untitled (Nature Morte) – are more abstract and suggestively gestural. Two drawings from the sixties – The Bather (Dana) and Study for “Blue Kitchen” – sunnily embrace the counterculture and 1960s modernism, respectively. Vaulting forward to the 1970s, the celebrated triptych Les Fleurs, isolating vases of flowers from separate perspectives, and Brown Interior with Rosine, presenting a woman sitting in drab comfort, assume a more austere, subdued, and regimented cast, perhaps a nod to the exigencies of age and the compulsion of preservation – or to fading glory.